Hello, I’m Philippe, and I am a Principal Solutions Architect helping customers with their usage of Docker. I started getting seriously interested in generative AI about two years ago. What interests me most is the ability to run language models (LLMs) directly on my laptop (For work, I have a MacBook Pro M2 max, but on a more personal level, I run LLMs on my personal MacBook Air M4 and on Raspberry Pis – yes, it’s possible, but I’ll talk about that another time).

Let’s be clear, reproducing a Claude AI Desktop or Chat GPT on a laptop with small language models is not possible. Especially since I limit myself to models that have between 0.5 and 7 billion parameters. But I find it an interesting challenge to see how far we can go with these small models. So, can we do really useful things with small LLMs? The answer is yes, but you need to be creative and put in a bit of effort.

I’m going to take a concrete use case, related to development (but in the future I’ll propose “less technical” use cases).

(Specific) Use Case: Code Writing Assistance

I need help writing code

Currently, I’m working in my free time on an open-source project, which is a Golang library for quickly developing small generative AI agents. It’s both to get my hands dirty with Golang and prepare tools for other projects. This project is called Nova; there’s nothing secret about it, you can find it here.

If I use Claude AI and ask it to help me write code with Nova: “I need a code snippet of a Golang Nova Chat agent using a stream completion.”

The response will be quite disappointing, because Claude doesn’t know Nova (which is normal, it’s a recent project). But Claude doesn’t want to disappoint me and will still propose something which has nothing to do with my project.

And it will be the same with Gemini.

So, you’ll tell me, give the “source code of your repository to feed” to Claude AI or Gemini. OK, but imagine the following situation: I don’t have access to these services, for various reasons. Some of these reasons could be confidentiality, the fact that I’m on a project where we don’t have the right to use the internet, for example. That already disqualifies Claude AI and Gemini. How can I get help writing code with a small local LLM? So as you guessed, with a local LLM. And moreover, a “very small” LLM.

Choosing a language model

When you develop a solution based on generative AI, the choice of language model(s) is crucial. And you’ll have to do a lot of technology watching, research, and testing to find the model that best fits your use case. And know that this is non-negligible work.

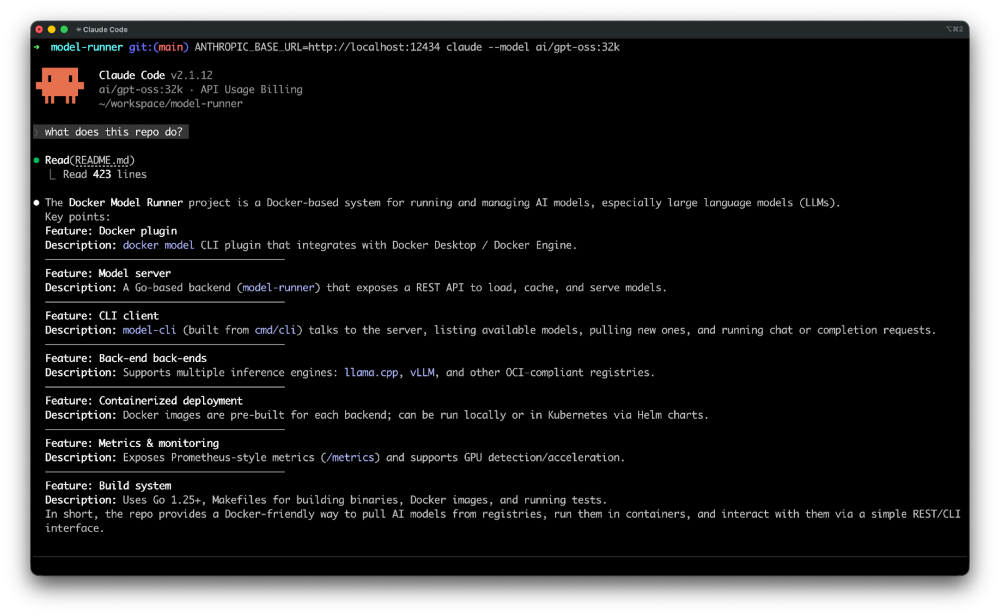

For this article (and also because I use it), I’m going to use hf.co/qwen/qwen2.5-coder-3b-instruct-gguf:q4_k_m, which you can find here. It’s a 3 billion parameter language model, optimized for code generation. You can install it with Docker Model Runner with the following command:

docker model pull hf.co/Qwen/Qwen2.5-Coder-3B-Instruct-GGUF:Q4_K_M

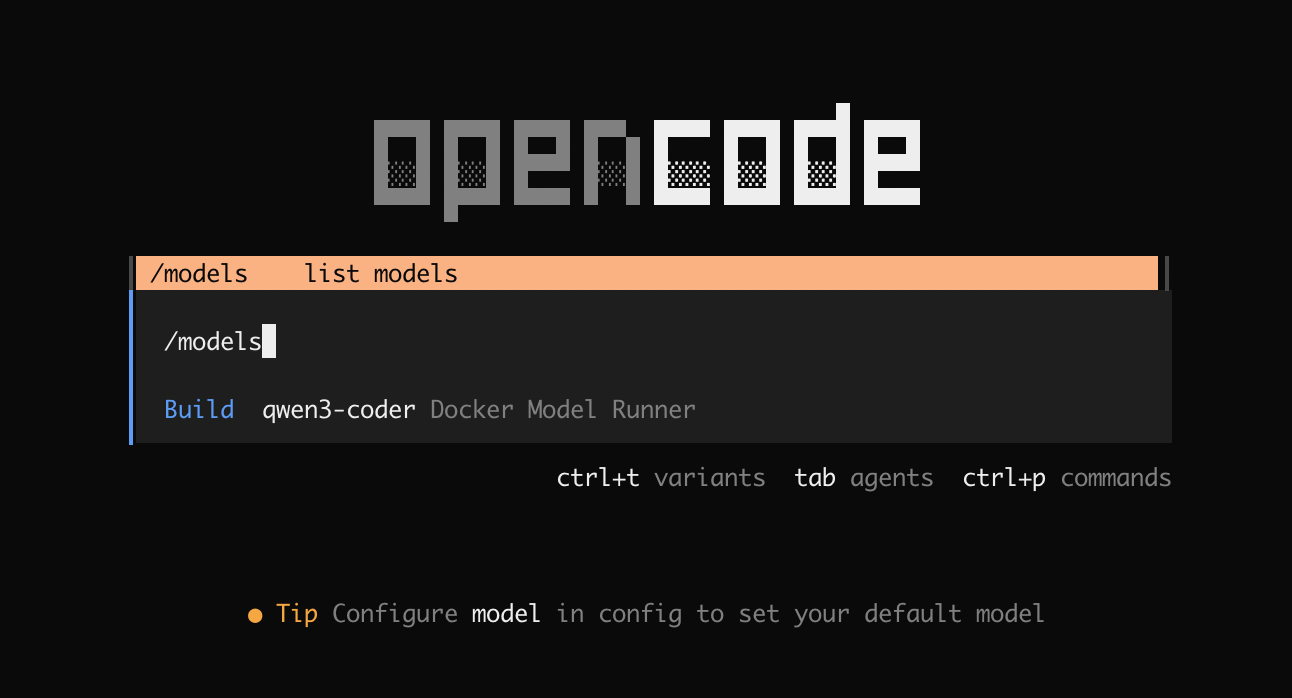

And to start chatting with the model, you can use the following command:

docker model run hf.co/qwen/qwen2.5-coder-3b-instruct-gguf:q4_k_m

Or use Docker Desktop:

So, of course, as you can see in the illustration above, this little “Qwen Coder” doesn’t know my Nova library either. But we’re going to fix that.

Feeding the model with specific information

For my project, I have a markdown file in which I save the code snippets I use to develop examples with Nova. You can find it here. For now, there’s little content, but it will be enough to prove and illustrate my point.

So I could add the entire content of this file to a user prompt that I would give to the model. But that will be ineffective. Indeed, small models have a relatively small context window. But even if my “Qwen Coder” was capable of ingesting all the content of my markdown file, it would have trouble focusing on my request and on what it should do with this information. So,

1st essential rule: when you use a very small LLM, the larger the content provided to the model, the less effective the model will be.

2nd essential rule: the more you keep the conversation history, the more the content provided to the model will grow, and therefore it will decrease the effectiveness of the model.

So, to work around this problem, I’m going to use a technique called RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation). The principle is simple: instead of providing all the content to the model, we’re going to store this content in a “vector” type database, and when the user makes a request, we’re going to search in this database for the most relevant information based on the user’s request. Then, we’re going to provide only this relevant information to the language model. For this blog post, the data will be kept in memory (which is not optimal, but sufficient for a demonstration).

RAG?

There are already many articles on the subject, so I won’t go into detail. But here’s what I’m going to do for this blog post:

My snippets file is composed of sections: a markdown title (## snippet name), possibly a description in free text, and a code block (golang … ).

I’m going to split this file by sections into chunks of text (we also talk about “chunks”),

Then, for each section I’m going to create an “embedding” (vector representation of text == mathematical representation of the semantic meaning of the text) with the ai/embeddinggemma:latest model (a relatively small and efficient embedding model). Then I’m going to store these embeddings (and the associated text) in an in-memory vector database (a simple array of JSON objects).

If you want to learn more about embedding, please read this article:Run Embedding Models and Unlock Semantic Search with Docker Model Runner

Diagram of the vector database creation process:

Similarity search and user prompt construction

Once I have this in place, when I make a request to the language model (so hf.co/qwen/qwen2.5-coder-3b-instruct-gguf:q4_k_m), I’m going to:

Create an embedding of the user’s request with the embedding model.

Compare this embedding with the embeddings stored in the vector database to find the most relevant sections (by calculating the distance between the vector representation of my question and the vector representations of the snippets). This is called a similarity search.

From the most relevant sections (the most similar), I’ll be able to construct a user prompt that includes only the relevant information and my initial request.

Diagram of the search and user prompt construction process:

So the final user prompt will contain:

The system instructions. For example: “You are a helpful coding assistant specialized in Golang and the Nova library. Use the provided code snippets to help the user with their requests.”

The relevant sections were extracted from the vector database.

The user’s request.

Remarks:

I explain the principles and results, but all the source code (NodeJS with LangchainJS) used to arrive at my conclusions is available in this project

To calculate distances between vectors, I used cosine similarity (A cosine similarity score of 1 indicates that the vectors point in the same direction. A cosine similarity score of 0 indicates that the vectors are orthogonal, meaning they have no directional similarity.)

You can find the JavaScript function I used here:

And the piece of code that I use to split the markdown snippets file:

Warning: embedding models are limited by the size of text chunks they can ingest. So you have to be careful not to exceed this size when splitting the source file. And in some cases, you’ll have to change the splitting strategy (fixed-size chunk,s for example, with or without overlap)

Implementation and results, or creating my Golang expert agent

Now that we have the operating principle, let’s see how to put this into music with LangchainJS, Docker Model Runner, and Docker Agentic Compose.

Docker Agentic Compose configuration

Let’s start with the Docker Agentic Compose project structure:

services:

golang-expert:

build:

context: .

dockerfile: Dockerfile

environment:

TERM: xterm-256color

HISTORY_MESSAGES: 2

MAX_SIMILARITIES: 3

COSINE_LIMIT: 0.45

OPTION_TEMPERATURE: 0.0

OPTION_TOP_P: 0.75

OPTION_PRESENCE_PENALTY: 2.2

CONTENT_PATH: /app/data

volumes:

– ./data:/app/data

stdin_open: true # docker run -i

tty: true # docker run -t

configs:

– source: system.instructions.md

target: /app/system.instructions.md

models:

chat-model:

endpoint_var: MODEL_RUNNER_BASE_URL

model_var: MODEL_RUNNER_LLM_CHAT

embedding-model:

endpoint_var: MODEL_RUNNER_BASE_URL

model_var: MODEL_RUNNER_LLM_EMBEDDING

models:

chat-model:

model: hf.co/qwen/qwen2.5-coder-3b-instruct-gguf:q4_k_m

embedding-model:

model: ai/embeddinggemma:latest

configs:

system.instructions.md:

content: |

Your name is Bob (the original replicant).

You are an expert programming assistant in Golang.

You write clean, efficient, and well-documented code.

Always:

– Provide complete, working code

– Include error handling

– Add helpful comments

– Follow best practices for the language

– Explain your approach briefly

Use only the information available in the provided data and your KNOWLEDGE BASE.

What’s important here is:

I only keep the last 2 messages in my conversation history, and I only select the 2 or 3 best similarities found at most (to limit the size of the user prompt):

HISTORY_MESSAGES: 2

MAX_SIMILARITIES: 3

COSINE_LIMIT: 0.45

You can adjust these values according to your use case and your language model’s capabilities.

The models section, where I define the language models I’m going to use:

models:

chat-model:

model: hf.co/qwen/qwen2.5-coder-3b-instruct-gguf:q4_k_m

embedding-model:

model: ai/embeddinggemma:latest

One of the advantages of this section is that it will allow Docker Compose to download the models if they’re not already present on your machine.

As well as the models section of the golang-expert service, where I map the environment variables to the models defined above:

models:

chat-model:

endpoint_var: MODEL_RUNNER_BASE_URL

model_var: MODEL_RUNNER_LLM_CHAT

embedding-model:

endpoint_var: MODEL_RUNNER_BASE_URL

model_var: MODEL_RUNNER_LLM_EMBEDDING

And finally, the system instructions configuration file:

configs:

– source: system.instructions.md

target: /app/system.instructions.md

Which I define a bit further down in the configs section:

configs:

system.instructions.md:

content: |

Your name is Bob (the original replicant).

You are an expert programming assistant in Golang.

You write clean, efficient, and well-documented code.

Always:

– Provide complete, working code

– Include error handling

– Add helpful comments

– Follow best practices for the language

– Explain your approach briefly

Use only the information available in the provided data and your KNOWLEDGE BASE.

You can, of course, adapt these system instructions to your use case. And also persist them in a separate file if you prefer.

Dockerfile

It’s rather simple:

FROM node:22.19.0-trixie

WORKDIR /app

COPY package*.json ./

RUN npm install

COPY *.js .

# Create non-root user

RUN groupadd –gid 1001 nodejs &&

useradd –uid 1001 –gid nodejs –shell /bin/bash –create-home bob-loves-js

# Change ownership of the app directory

RUN chown -R bob-loves-js:nodejs /app

# Switch to non-root user

USER bob-loves-js

Now that the configuration is in place, let’s move on to the agent’s source code.

Golang expert agent source code, a bit of LangchainJS with RAG

The JavaScript code is rather simple (probably improvable, but functional) and follows these main steps:

1. Initial configuration

Connection to both models (chat and embeddings) via LangchainJS

Loading parameters from environment variables

2. Vector database creation (at startup)

Reading the snippets.md file

Splitting into sections (chunks)

Generating an embedding for each section

Storing in an in-memory vector database

3. Interactive conversation loop

The user asks a question

Creating an embedding of the question

Similarity search in the vector database to find the most relevant snippets

Construction of the final prompt with: history + system instructions + relevant snippets + question

Sending to the LLM and displaying the response in streaming

Updating the history (limited to the last N messages)

import { ChatOpenAI } from "@langchain/openai";

import { OpenAIEmbeddings} from '@langchain/openai';

import { splitMarkdownBySections } from './chunks.js'

import { VectorRecord, MemoryVectorStore } from './rag.js';

import prompts from "prompts";

import fs from 'fs';

// Define [CHAT MODEL] Connection

const chatModel = new ChatOpenAI({

model: process.env.MODEL_RUNNER_LLM_CHAT || `ai/qwen2.5:latest`,

apiKey: "",

configuration: {

baseURL: process.env.MODEL_RUNNER_BASE_URL || "http://localhost:12434/engines/llama.cpp/v1/",

},

temperature: parseFloat(process.env.OPTION_TEMPERATURE) || 0.0,

top_p: parseFloat(process.env.OPTION_TOP_P) || 0.5,

presencePenalty: parseFloat(process.env.OPTION_PRESENCE_PENALTY) || 2.2,

});

// Define [EMBEDDINGS MODEL] Connection

const embeddingsModel = new OpenAIEmbeddings({

model: process.env.MODEL_RUNNER_LLM_EMBEDDING || "ai/embeddinggemma:latest",

configuration: {

baseURL: process.env.MODEL_RUNNER_BASE_URL || "http://localhost:12434/engines/llama.cpp/v1/",

apiKey: ""

}

})

const maxSimilarities = parseInt(process.env.MAX_SIMILARITIES) || 3

const cosineLimit = parseFloat(process.env.COSINE_LIMIT) || 0.45

// —————————————————————-

// Create the embeddings and the vector store from the content file

// —————————————————————-

console.log("========================================================")

console.log(" Embeddings model:", embeddingsModel.model)

console.log(" Creating embeddings…")

let contentPath = process.env.CONTENT_PATH || "./data"

const store = new MemoryVectorStore();

let contentFromFile = fs.readFileSync(contentPath+"/snippets.md", 'utf8');

let chunks = splitMarkdownBySections(contentFromFile);

console.log(" Number of documents read from file:", chunks.length);

// ————————————————-

// Create and save the embeddings in the memory vector store

// ————————————————-

console.log(" Creating the embeddings…");

for (const chunk of chunks) {

try {

// EMBEDDING COMPLETION:

const chunkEmbedding = await embeddingsModel.embedQuery(chunk);

const vectorRecord = new VectorRecord('', chunk, chunkEmbedding);

store.save(vectorRecord);

} catch (error) {

console.error(`Error processing chunk:`, error);

}

}

console.log(" Embeddings created, total of records", store.records.size);

console.log();

console.log("========================================================")

// Load the system instructions from a file

let systemInstructions = fs.readFileSync('/app/system.instructions.md', 'utf8');

// —————————————————————-

// HISTORY: Initialize a Map to store conversations by session

// —————————————————————-

const conversationMemory = new Map()

let exit = false;

// CHAT LOOP:

while (!exit) {

const { userMessage } = await prompts({

type: "text",

name: "userMessage",

message: `Your question (${chatModel.model}): `,

validate: (value) => (value ? true : "Question cannot be empty"),

});

if (userMessage == "/bye") {

console.log(" See you later!");

exit = true;

continue

}

// HISTORY: Get the conversation history for this session

const history = getConversationHistory("default-session-id")

// —————————————————————-

// SIMILARITY SEARCH:

// —————————————————————-

// ————————————————-

// Create embedding from the user question

// ————————————————-

const userQuestionEmbedding = await embeddingsModel.embedQuery(userMessage);

// ————————————————-

// Use the vector store to find similar chunks

// ————————————————-

// Create a vector record from the user embedding

const embeddingFromUserQuestion = new VectorRecord('', '', userQuestionEmbedding);

const similarities = store.searchTopNSimilarities(embeddingFromUserQuestion, cosineLimit, maxSimilarities);

let knowledgeBase = "KNOWLEDGE BASE:n";

for (const similarity of similarities) {

console.log(" CosineSimilarity:", similarity.cosineSimilarity, "Chunk:", similarity.prompt);

knowledgeBase += `${similarity.prompt}n`;

}

console.log("n Similarities found, total of records", similarities.length);

console.log();

console.log("========================================================")

console.log()

// ————————————————-

// Generate CHAT COMPLETION:

// ————————————————-

// MESSAGES== PROMPT CONSTRUCTION:

let messages = [

…history,

["system", systemInstructions],

["system", knowledgeBase],

["user", userMessage]

]

let assistantResponse = ''

// STREAMING COMPLETION:

const stream = await chatModel.stream(messages);

for await (const chunk of stream) {

assistantResponse += chunk.content

process.stdout.write(chunk.content);

}

console.log("n");

// HISTORY: Add both user message and assistant response to history

addToHistory("default-session-id", "user", userMessage)

addToHistory("default-session-id", "assistant", assistantResponse)

}

// Helper function to get or create a conversation history

function getConversationHistory(sessionId, maxTurns = parseInt(process.env.HISTORY_MESSAGES)) {

if (!conversationMemory.has(sessionId)) {

conversationMemory.set(sessionId, [])

}

return conversationMemory.get(sessionId)

}

// Helper function to add a message to the conversation history

function addToHistory(sessionId, role, content) {

const history = getConversationHistory(sessionId)

history.push([role, content])

// Keep only the last maxTurns conversations

const maxTurns = parseInt(process.env.HISTORY_MESSAGES) // Adjust this value based on your needs

if (history.length > maxTurns * 2) { // *2 because each turn has user & assistant message

history.splice(0, 2) // Remove oldest turn (user + assistant messages)

}

}

You can find it here:

All that’s left is to launch to verify my hypotheses

In the project folder, run the following command:

docker compose up –build –no-log-prefix -d

Then connect to the container and launch the application:

docker compose exec golang-expert /bin/bash

node index.js

Nova Chat Agent with streaming completion

Once the application started, it’s time to ask our question to our Golang expert agent in development with the Nova library:

========================================================

Embeddings model: ai/embeddinggemma:latest

Creating embeddings…

Number of documents read from file: 4

Creating the embeddings…

Embeddings created, total of records 4

========================================================

? Your question (hf.co/qwen/qwen2.5-coder-3b-instruct-gguf:q4_k_m): › I need a code snippet of a Golang Nova Chat agent using a stream completion

After a quick similarity search, our agent found two relevant snippets in the vector database. And it was able to provide me with complete, functional, and commented code to answer my request:

Certainly! Below is a complete, working Go code snippet for a Nova Chat agent that uses streaming completion. This example demonstrates how to set up an agent with the necessary configurations and generate a stream completion response.

“`go

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"github.com/snipwise/nova/nova-sdk/agents"

"github.com/snipwise/nova/nova-sdk/agents/chat"

"github.com/snipwise/nova/nova-sdk/messages"

"github.com/snipwise/nova/nova-sdk/messages/roles"

"github.com/snipwise/nova/nova-sdk/models"

)

func main() {

ctx := context.Background()

// Create a new chat agent with streaming capabilities

agent, err := chat.NewAgent(

ctx,

agents.Config{

EngineURL: "http://localhost:12434/engines/llama.cpp/v1",

SystemInstructions: "You are Bob, a helpful AI assistant.",

KeepConversationHistory: true,

},

models.Config{

Name: "ai/qwen2.5:1.5B-F16",

Temperature: models.Float64(0.8),

},

)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

// Generate a stream completion response

result, err := agent.GenerateStreamCompletion(

[]messages.Message{

{Role: roles.User, Content: "Who is James T Kirk?"},

},

func(chunk string, finishReason string) error {

// Simple callback that receives strings only

if chunk != "" {

fmt.Print(chunk)

}

if finishReason == "stop" {

fmt.Println()

}

return nil

},

)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

// Print the final response and finish reason

fmt.Println("Final Response:", result.Response)

fmt.Println("Finish Reason:", result.FinishReason)

}

### Explanation:

1. **Imports**: The code imports necessary packages from the Nova SDK to interact with chat agents.

2. **Context**: A context is created using `context.Background()` to manage the lifecycle of requests.

3. **Agent Creation**:

– An agent is created using `chat.NewAgent` with specified configurations:

– `EngineURL`: The URL of the engine to use for generating text.

– `SystemInstructions`: Instructions for the AI assistant, such as who Bob is.

– `KeepConversationHistory`: Whether to keep a history of previous messages.

4. **Model Configuration**:

– A model configuration is provided with:

– `Name`: The name of the model to use.

– `Temperature`: Controls the randomness of the output (higher values make responses more random).

– `MaxTokens`: Limits the maximum number of tokens in the response.

5. **Stream Completion Generation**:

– The `GenerateStreamCompletion` method is called with a list of messages and a callback function that processes each chunk of text as it arrives.

– The callback prints chunks to the console until the finish reason is "stop", indicating the completion has been reached.

6. **Output**:

– The final response and finish reason are printed after the stream completes.

This code snippet demonstrates how to set up a streaming chat agent using Nova, allowing you to receive text responses incrementally as they become available.

I then asked other questions.

Nova Structured Agent

This time, I asked for a structured agent: “I need a code snippet of a Nova Structured Agent.”

And the result was conclusive:

Extract from the response:

Certainly! Below is a complete, working example of a Nova Structured Agent in Go. This agent will generate structured data about a specified country based on the user's input.

“`go

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"github.com/snipwise/nova/nova-sdk/agents"

"github.com/snipwise/nova/nova-sdk/agents/structured"

"github.com/snipwise/nova/nova-sdk/messages"

"github.com/snipwise/nova/nova-sdk/messages/roles"

"github.com/snipwise/nova/nova-sdk/models"

)

type Country struct {

Name string `json:"name"`

Capital string `json:"capital"`

Population int `json:"population"`

Languages []string `json:"languages"`

}

func main() {

ctx := context.Background()

// Create a new Structured Agent

agent, err := structured.NewAgent[Country](

ctx,

agents.Config{

EngineURL: "http://localhost:12434/engines/llama.cpp/v1",

SystemInstructions: `

Your name is Bob.

You are an assistant that answers questions about countries around the world.

`,

},

models.Config{

Name: "hf.co/menlo/jan-nano-gguf:q4_k_m",

Temperature: models.Float64(0.0),

},

)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

// Generate structured data about Canada

response, finishReason, err := agent.GenerateStructuredData([]messages.Message{

{Role: roles.User, Content: "Tell me about Canada."},

})

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

// Print the generated country information

fmt.Println("Country Name:", response.Name)

fmt.Println("Capital:", response.Capital)

fmt.Println("Population:", response.Population)

fmt.Println("Languages:", strings.Join(response.Languages, ", "))

}

### Explanation:

1. **Imports**: The code imports necessary packages from the Nova SDK to interact with agents and models.

2. **Country Struct**: A simple struct `Country` is defined to represent the data structure expected by the agent.

3. **Main Function**:

– A context is created using `context.Background()`.

– A new Structured Agent is created for generating structured data about countries.

– The system instructions are set to provide a friendly greeting and instruction on answering questions about countries.

– The model configuration specifies the engine URL, temperature, and other parameters.

4. **GenerateStructuredData Method**: This method generates structured data based on the user's input. It takes an array of messages as input, where each message has a role (e.g., `User`) and content (e.g., "Tell me about Canada").

5. **Error Handling**: The code includes error handling to ensure that any issues during agent creation or data generation are properly caught and reported.

6. **Output**: The generated country information is printed, including the name, capital, population, and languages.

This example demonstrates how to use a Nova Structured Agent to generate structured data about countries based on user input. You can modify the system instructions and model configuration as needed for your specific use case.

Then, I moved on to the next question.

Nova RAG Agent with vector store. Be careful with your similarity settings!

This time, I asked for a “RAG” agent: “I need a snippet of a Nova RAG agent with a vector store.”

And once again, I got a relevant response.

However, when I tried with this question (after restarting the agent to start from a clean base without conversation history): “I need a snippet of a Nova RAG agent.”

The similarity search returned no relevant results (because the words “vector store” were not present in the snippets). And the agent responded with generic code that had nothing to do with Nova or was using code from Nova Chat Agents.

There may be several possible reasons:

The embedding model is not suitable for my use case,

The embedding model is not precise enough,

The splitting of the code snippets file is not optimal (you can add metadata to chunks to improve similarity search, for example, but don’t forget that chunks must not exceed the maximum size that the embedding model can ingest).

In that case, there’s a simple solution that works quite well: you lower the similarity thresholds and/or increase the number of returned similarities. This allows you to have more results to construct the user prompt, but be careful not to exceed the maximum context size of the language model. And you can also do tests with other “bigger” LLMs (more parameters and/or larger context window).

In the latest version of the snippets file, I added a KEYWORDS: … line below the markdown titles to help with similarity search. Which greatly improved the results obtained.

Conclusion

Using “Small Language Models” (SLM) or “Tiny Language Models” (TLM) requires a bit of energy and thought to work around their limitations. But it’s possible to build effective solutions for very specific problems. And once again, always think about the context size for the chat model and how you’ll structure the information for the embedding model. And by combining several specialized “small agents”, you can achieve very interesting results. This will be the subject of future articles.

Learn more

Check out Docker Model Runner

Learn more about Docker Agentic Compose

Read more about embedding in our recent blog Run Embedding Models and Unlock Semantic Search with Docker Model Runner

Quelle: https://blog.docker.com/feed/