Akash Iyer / Via BuzzFeed India

At 8 PM on November 8, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi unexpectedly banned 86% of the country’s legal tender from circulation. The goal was to wipe out “black money” —&x200A;a term used in India for cash that’s stashed outside the banking system to evade taxes. Old notes of Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,000 would no longer be legal. Instead, the government would issue new, redesigned Rs. 2,000 notes.

Hours after the Prime Ministerial bombshell, the rumors started flying fast and thick over WhatsApp, the Facebook-owned instant messaging app used by more than 160 million Indians: the new notes would include an embedded GPS chip that would allow the government to track down hoarders.

Twitter: @Nisha__Hindu

Soon a video purporting to show one of these GPS notes being tracked on Google Maps went viral on WhatsApp, and then Facebook. And &x200A;less than 24 hours after the rumor started&x200A;, &x200A;Zee News, a leading Hindi television news channel, ran a 90-second report about the high-tech note, leading the country’s reserve bank to finally debunk it.

The United States is currently experiencing a fake news crisis – bogus news articles disguised to look like real ones to mislead people, influence public opinion, and/or to simply use their massive reach to reap advertising profits. These operations are sophisticated, data-driven and highly targeted. But in countries like India where internet penetration and literacy still lag far behind the US, misinformation tends to have a more grassroots quality. Twitter is a fertile ground for all kinds of rumor mongering, but with just over 30 million users in the country, its impact is limited.

“Our problem is WhatsApp, because it’s fast, simple, and much more intimate compared to Facebook.”

The primary vector for the spread of misinformation in India is WhatApp. The instant messenger is fast, free, and runs on nearly all of India’s 300 million smartphones. It’s also encrypted end-to-end, which means it’s nearly impossible to track what flows through it. Its real-world ramifications, nonetheless, can be brutal.

In November, WhatsApp rumors of a salt shortage sparked panic in at least four Indian states and caused stampedes outside grocery shops as people rushed to stock up. The government eventually debunked the rumours – but not before a woman died.

A Different Kind of Fake News

India’s misinformation problem predates the internet. In the early ‘90s, rabble-rousers in northern India trying to stir up tensions in Hindu and Muslim communities would mass-produce cassette recordings full of fake gunfire, screams, and chants of “Allah-ho-Akbar,” and then play them in car stereos at full volume in the dead of the night to incite communal violence.

And once the internet and social media came to the country, hoaxes took on a life of their own. In 2008, Pepsi was forced to publicly rebut a video that claimed that its Indian subsidiary manufactured Kurkure — Indian Cheetos — out of plastic. A few years later, makers of Frooti, a popular mango drink, started offering guided tours of their facilities after a rumour about the beverage containing HIV-positive blood went viral. In 2015, Mumbai’s police commissioner set up a hotline for anxious parents and urged people to ignore WhatsApp rumors, which claimed that gangs of women were kidnapping school children.

“I think it’s unfair to draw a direct parallel between the kind of organized fake news industry we saw in the lead up to the US elections and what happens in India,” said the social media strategist of a prominent political party in Delhi who did not wish to be named. “Our problem is WhatsApp, because it’s fast, simple, and much more intimate compared to Facebook. There’s more incentive for perpetrators of misinformation in India to distribute it over WhatsApp than Facebook because the chances of having real-world impact through WhatsApp are higher.”

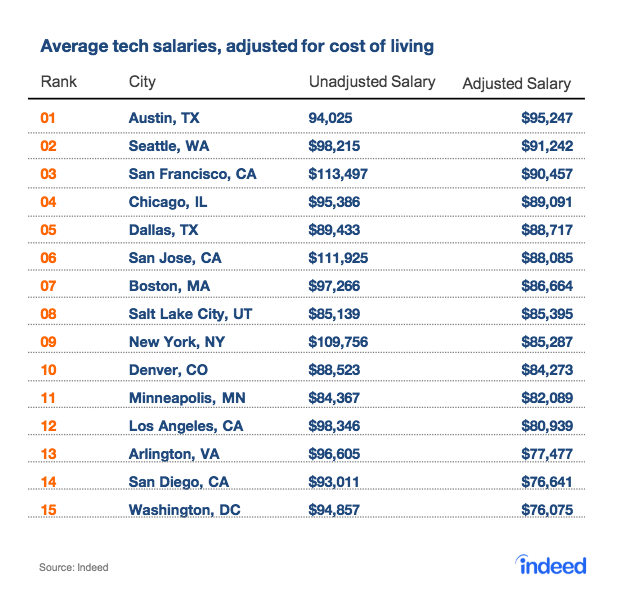

What is also a disincentive is how little average revenue each Indian user generates for Facebook annually, despite the fact that the country is Facebook’s largest market outside the United States. According to the company’s own numbers, each user in the Asia-Pacific region generates less than $8 annually compared to a US user who generates $62. That makes India a less attractive target for people like teens in Macedonia, for instance, who earned thousands of dollars in advertising revenue peddling pro-Trump fake stories on Facebook to millions of Americans.

A Nationalist Wave

“There's been a sharp increase in WhatsApp forwards that are just propaganda.”

In 2014, Narendra Modi, a right-wing politician known for his close ties to Hindu supremacist group RSS, won by a landslide to become the Prime Minister of India. Like Trump, Modi is a polarizing figure – and his rise to power birthed thousands of social media trolls and organized misinformation campaigns.

“Everything changed,” said author Rupa Gulab, who is an outspoken Modi critic. “The hoaxes that went viral a few years before were just silly, but with Modi and his fanatics, there’s been a sharp increase in the amount of WhatsApp forwards you receive that are just propaganda.”

The build-up started while Modi was still campaigning in 2014. In January of that year, a quote about Modi attributed to WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange went viral on Twitter, WhatsApp, and Facebook, boosted by shares from members of Modi’s party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Twitter: @mrsgandhi

WikiLeaks denied the quote.

Twitter: @wikileaks

That didn’t stop the wave of Modi-related forwards on WhatsApp.

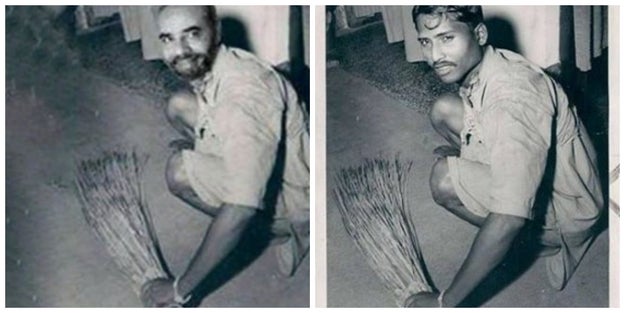

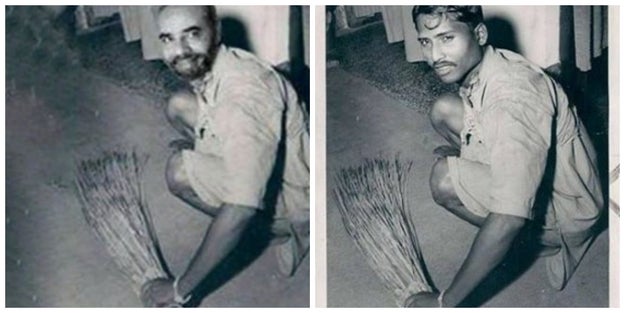

In October 2015, a photo of Modi sweeping the floor “during an RSS rally in 1988”&x200A; — &x200A;an attempt to highlight the Prime Minister’s humble roots &x200A;— &x200A;blew up. Later it became clear the image was Photoshopped.

A photo of Prime Minister Modi sweeping the floor “during an RSS rally in 1988” (left) was found to be Photoshopped from the original picture (right) in 2015.

Last year, India’s Press Information Bureau, an agency that manages government communication with the media, was left red-faced after it published a Photoshopped picture of the Prime Minister looking out on a flooded town in the flood-hit state of Tamil Nadu via its official Twitter handle. A new hashtag PhotoshopSarkar&x200A;—&x200A;Photoshop Government&x200A;—&x200A;was born.

Twitter: @SusegadGoan

And in August, Modi himself had to debunk a viral story that claimed that he had urged citizens to boycott Chinese-made firecrackers.

Twitter: @pmoindia

More recently, in a thread that went viral, Twitter user @samjawed65 deconstructed how an uncorroborated pro-government report in a mainstream Indian publication ended up in an aggregation echo chamber with half a dozen other media outlets re-reporting it, until the Huffington Post finally debunked it as fake news.

A recently published book details how the BJP deliberately created abusive social media campaigns using both WhatsApp and Twitter to troll prominent Indians and spread lies.

“[It’s clear] how seriously the political Hindu Right in India takes the online space as an ideological battlefield,” Rohit Chopra, a media studies professor at Santa Clara University who is working on a book about Hindu nationalism and new media, told BuzzFeed News. “They have invested money in it, they have mechanisms for flooding platforms like Twitter with messages either promoting their view or attacking contrary views, and they seem to employ a significant number of people in different capacities to manage this space.”

Krishna Prasad, former editor-in-chief of Indian news weekly Outlook, agrees. Once, Prasad recalls, a social media strategist asked him during a meeting with BJP politicians, “What have you gotten to trend on Twitter today?” “There are clearly people in India’s political parties buying hashtags and trying to influence trending topics,” he told BuzzFeed News.

“Individuals trying to influence trending topics are considered spammers and may have their accounts temporarily or permanently suspended,” a Twitter spokesperson told BuzzFeed News, and pointed to Twitter’s page that outlines rules for trending topics.

Dark Social

In November, local newspapers reported that a doctor in the eastern state of Bihar had died of a cardiac arrest after income tax officials raided his house and seized illegal currency – except it wasn’t true. The rumors had first spread on WhatsApp before trickling up to the local media that ran the story without verification. Eventually, the doctor had to call a press conference to declare he was still alive and there had be no raid.

WhatsApp groups are the connective tissue that bind most Indians.

India is the number one market for WhatsApp in the world. The instant messenger is the most popular messaging platform that connects everyone from school friends to India’s bureaucrats. WhatsApp groups are the connective tissue that bind most Indians — but they are also notorious for being hotbeds of spammy forwards and hoaxes.

“Most Indians belong to tight-knight groups on WhatsApp such as a friends group and a family group,” said Harsh Taneja, an assistant professor at the Missouri School of Journalism whose research focuses on audience behaviour and internet use. “But digital networks like WhatsApp are designed to connect us tightly with groups of acquittances too, who we may not otherwise have interacted with frequently.”

These “weak ties”, as Taneja calls them, are the reason why information spreads rapidly on closed networks like WhatsApp. “Most misinformation that originates within WhatsApp finds its way through this tight-knit network of weak ties,” Taneja said. But it’s tough to analyze WhatsApp. The messaging platform is encrypted end-to-end with no API, algorithms, or trending topics&x200A; – which means that it’s virtually impossible to track exactly how content spreads through it.

A spokesperson at the Hindu Sena, a Hindu nationalist party that celebrated Donald Trump’s victory in Delhi in December, told BuzzFeed News that he is a part of more than 50 right-wing WhatsApp groups, and sends “thousands of WhatsApp forwards around the country every day.”

Last year, police in different Indian states arrested half a dozen admins of WhatsApp groups, charging them with the crime of spreading misleading information, even though an admin has no control over what other members post in a group they belong to.

“We need to ask tough questions of Facebook, Twitter and Google in an Indian context.”

Other times, Indian authorities have resorted the using the bluntest weapon possible: turning off mobile internet entirely. In the first nine months of 2016, the Indian government turned off the internet 22 times in various parts of the country – including a four-month stretch in violence-ridden Kashmir – simply to prevent rumors from spreading over WhatsApp.

“We need to ask tough questions of Facebook, Twitter and Google in an Indian context, just like they are being brought to book in America,” said Prasad. “In a country like India that is so diverse and culturally different from the US, these companies cannot get away with saying that we are just platforms any longer.”

Facebook declined to comment on WhatsApp in the context of fake news. A Facebook spokesperson instead directed BuzzFeed News to CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s post on the topic. “We’ve made significant progress,” it says. “But there is more work to be done.”

Quelle: <a href="Viral WhatsApp Hoaxes Are India’s Own Fake News Crisis“>BuzzFeed