Nevermind The Russians, Meet The Bot King Who Helps Trump Win Twitter

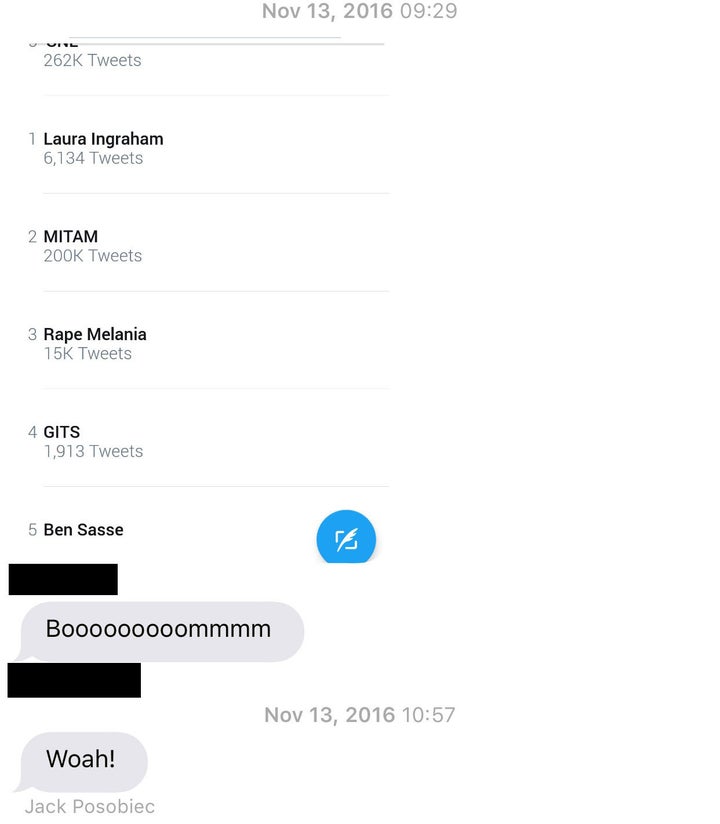

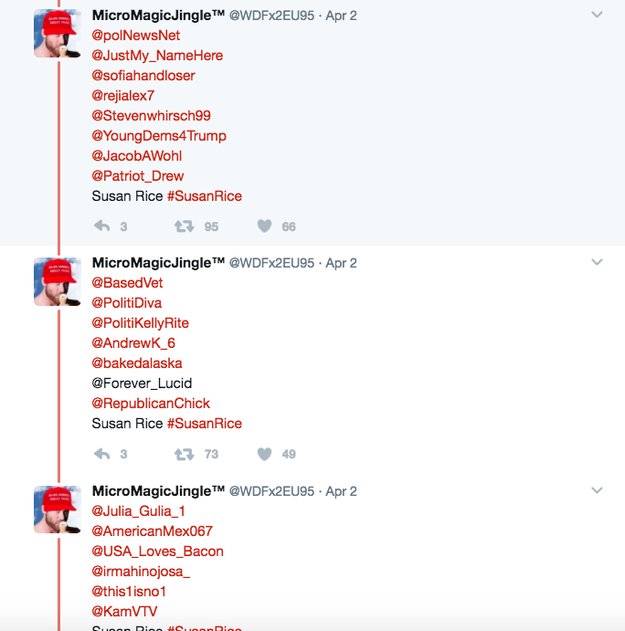

At 7:23 on Sunday evening, the conservative internet personality Mike Cernovich tweeted that former national security adviser Susan Rice had requested the “unmasking” of Americans connected to the Trump campaign who were incidentally mentioned in surveillance readouts. At 7:30, the owner of the Twitter account MicroMagicJingleTM noticed, and began blasting out dozens of tweets and retweets about the story.

“Would be nice to get 'Susan Rice&039; trending,” he tweeted at 8:16. And then, he made exactly that happen.

MicroMagicJingleTM is the latest incarnation of MicroChip, a notorious pro-Trump Twitter ringleader once described by a Republican strategist as the “Trumpbot overlord.” He has been suspended from the service so frequently, he can’t recall the exact number of times. A voluminous tweeter, his specialty is making hashtags trend. Over the next 24 hours, following his own call to arms, MicroChip tweeted or retweeted more than 300 times about Rice, everything from a photoshopped image of Donald Trump eating her head out of a taco bowl to demands that she die in jail, almost always accompanied by the tag #SusanRice. Meanwhile, in massive threaded tweets and DM groups, he implored others to do likewise.

By 9 a.m. Monday, the tag was being tweeted nearly 20,000 times an hour, and was trending on Twitter; by 11 a.m., 34,000 an hour. (As of Tuesday morning, the tag was still trending, partially thanks to a tweet from Donald Trump Jr.) At 4:48 p.m. Monday, 18-odd hours after he started his campaign, MicroChip was ready to call it a success:

Before? What did he mean by “before”? Before the election, before the campaign, and long since before “Russian interference” was the mantra of every political consultant, British former member of parliament, and American senator turned Tolstoy enthusiast, MicroChip has been figuring out how to make pro-Trump tags go viral on Twitter. When people talk about Russian Twitter bots, they are, very likely, sometimes talking about his work. They’ve ranged from the innocuously rah-rah (#TrumpTrain) to the wildly xenophobic (#Rapefugees) to the extremely unconfirmed (#cruzsexscandal and #hillarygropedme). What they’ve all had in common is a method, the focus of speculation for nearly a year, and a chief promulgator, MicroChip, about whom little is known.

Indeed, MicroChip, who operates behind a VPN (a special secure network that obscures his location), is an object of fascination and fear, even among some of his political and ideological fellow travelers, who hope not to end up on the wrong side of one of his Twitter campaigns. One conservative observer of the alt-right, who spoke to BuzzFeed on the condition that his name not be used, claimed he once hired private investigators to trace him.

“You can’t,” the observer wrote in a text message. “He’s too good.”

Unconvincing internet investigations have suggested that MicroChip may be anyone from the prominent alt-righter Baked Alaska to Justin McConney, the director of social media for the Trump Organization, to a shadowy Russian puppet master.

But in an interview with BuzzFeed News — his first with a media organization — MicroChip said the truth, both about his identity and the method he developed for spreading pro-Trump messages on Twitter, is far more prosaic. Though he would not divulge his real name or corroborate his claim, MicroChip said that he is a freelance mobile software developer in his early thirties and lives in Utah. In a conversation over the gaming chat platform Discord, MicroChip, who speaks unaccented, idiomatic American English, said that he guards his identity so closely for two reasons: first, because he fears losing contract work due to his beliefs, and second, because of what he calls an “uninformed” discourse in the media and Washington around Russian influence and botting.

“I feel like I&039;m a scientist showing electricity to natives that have been convinced electricity is created by Satan, so they murder the scientist,” he said.

Indeed, in a national atmosphere charged by unproven accusations about a massive network of Russian social media influence, the story of how MicroChip helped build the most notorious pro-Trump Twitter network seems almost mundane, less a technologically daunting intelligence operation than a clever patchworking of tools nearly any computer-literate person could manage. It also suggests that some of the current Russian Trumpbot hysteria may be, well, a hysteria.

“It’s all us, not Russians,” MicroChip said. “And we’re not going to stop.”

MicroChip claims he was a longtime “staunch liberal” who turned to Twitter in the aftermath of the November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, and “found out that I didn’t like what was going on. So I redpilled myself.” Through Twitter, he found a network of other people who thought liberal politicians had blindly acceded to PC culture, and who had found a champion in Donald Trump. In his early days on the platform, MicroChip said, he started “testing,” dabbling in anti-PC tags like Rapefugees and seeing what went viral. His experience as a mobile developer had exposed him to the Twitter API, and a conversation with a blogger who ran social media bots convinced him he could automate the Twitter trending process.

“Micro is a true believer alt-right guy,” wrote the alt-right observer who had MicroChip investigated. “He’s brilliant and is not LARPing. His tech skills are real as is his opsec.”

As MicroChip found other like-minded accounts, he said, they began to organize themselves into enormous, 50-person direct message groups. Within these groups, members would distribute content from the Drudge Report and Reddit’s r/The_Donald subreddit, then tweet it with a commonly decided hashtag, and retweet one another’s tweets ad infinitum. MicroChip called the DM rooms, simply, “retweet groups,” and by September of last year, there were 15 of them. Some of the groups were chock-full of egg and anime avatars, according to MicroChip, but others were composed of Christian conservatives or hardcore Zionists. Taken together, they were like a strange Twitter mirror image of the Trump coalition.

MicroChip added automation to these dedicated DM groups, which he insisted are populated entirely by real people with real accounts. He started using AddMeFast, a kind of social media currency exchange, in which people can retweet or like other tweets in exchange for points that they can then can spend to list their own content (such as pro-Trump hashtagged tweets) to be promoted. You can also buy these points, and an investment of several hundred dollars, according to MicroChip, can yield thousands or even tens of thousands of retweets.

A third component of MicroChip’s blended army of DM groups and crowdsourced social media signal boosters were simple Google script bots. These bots, which MicroChip said “you don’t have to do any programming at all to run,” can be programmed to find and like or retweet tweets featuring certain terms or hashtags.

At its height, MicroChip said, the network he helped create could reliably generate 35,000 retweets a day.

“It’s high volume and it takes work,” he said. “You can’t take a break — you sit at the screen waiting for breaking news 12 hours per day when you’re knee-deep in it.” It’s hard work: MicroChip would sometimes reach his daily limit of 1,000 tweets a day, sometimes taking Adderall to focus — though he added, “Shaping a message is exhilarating.”

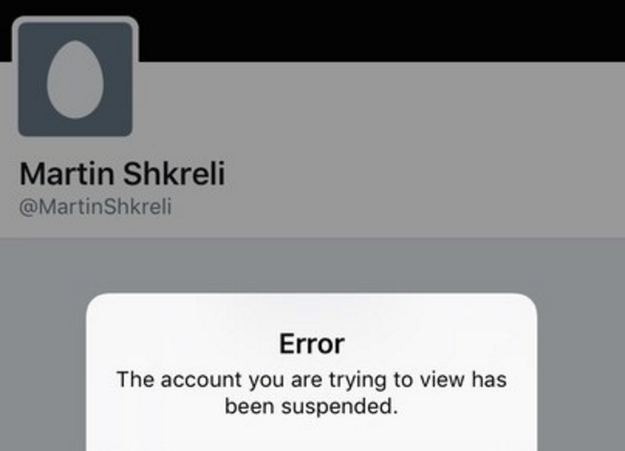

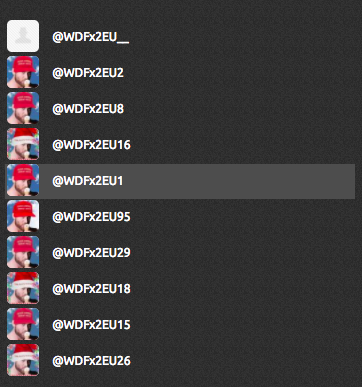

Along the way, Twitter started to suspend MicroChip’s accounts — first his original handle @WDfx2EU, then subsequent variations, each started with a link to his Keybase page to verify his identity, and each presided over by the same avatar: the Instagram hunk Brock O’Hurn wearing a Make America Great Again hat and eating an ice cream cone. MicroChip showed BuzzFeed dozens of other accounts he owns, ready to activate if and when his current account, @WDFx2EU95, gets suspended.

While it may take work to stay active, MicroChip says he has has an ideal platform in Twitter with which to shape a message. “Twitter is easier [than other social networks] and more volatile,” he said. “Emotions run high at 140 characters. The chaos is perfect.”

MicroChip is well aware that many of the tags and stories he promotes haven’t been proven or aren’t true. He’s thrown his network behind #Pizzagate and #SpiritCooking. And days before the election, he posted a tweet to r/The_Donald about an alleged plot by then-president Obama and Hillary Clinton to have Trump assassinated in Reno.

“This ignorant shit needs to be stopped,” replied one user.

“I can make whatever claims I want to make,” MicroChip shot back. “That’s how this game works.”

It’s true that MicroChip can make any claim he wants, and it’s impossible to say that his stories about his identity are true: He could be Vladimir Putin. But multiple aspects of his method can be confirmed: MicroChip provided records of his activity on AddMeFast to BuzzFeed News, alt-right sources confirmed that he was a consistent presence in their DM groups, and the day after the election multiple pro-Trump accounts thanked him for his efforts:

“Micro put in serious work during the election and I really respect his lack of ego,” said another source within the Trump internet world who has worked closely with MicroChip. “He&039;s anonymous and doesn’t care about the credit.”

Indeed, the fact that MicroChip’s network — that much pro-Trump internet activity — is now reflexively assumed to be part of a Russian influence campaign is one of the reasons MicroChip wanted to explain how he helped build it: not to take credit (he repeatedly referred to the network as a group effort) but to set the record straight.

“I’m not Russian,” MicroChip said. “I don’t work for Trump. There could very well be Russian bots. I just never saw them and we were in this deep. We’ve been on Twitter every day for the last year and a half. I haven’t seen any bots that I don’t know who they are.”

And if MicroChip is a Russian agent, it’s worth wondering why he, nearly three months into the Trump presidency, has plans to expand his network in the coming weeks with a new set of botting tools.

In a Twitter argument Monday with the Brooklyn developer Nathan Bernard, MicroChip teased that his network is about to get much, much bigger.

“The botnet [is] about to happen 10 X in about a week,” he wrote. “Get ready.”

Quelle: <a href="Nevermind The Russians, Meet The Bot King Who Helps Trump Win Twitter“>BuzzFeed