Making the Most of Your Docker Hardened Images Enterprise Trial – Part 3

Customizing Docker Hardened Images

In Part 1 and Part 2, we established the baseline. You migrated a service to a Docker Hardened Image (DHI), witnessed the vulnerability count drop to zero, and verified the cryptographic signatures and SLSA provenance that make DHI a compliant foundation.

But no matter how secure a base image is, it is useless if you can’t run your application on it. This brings us to the most common question engineers ask during a DHI trial: what if I need a custom image?

Hardened images are minimal by design. They lack package managers (apt, apk, yum), utilities (wget, curl), and even shells like bash or sh. This is a security feature: if a bad actor breaks into your container, they find an empty toolbox.

However, developers often need these tools during setup. You might need to install a monitoring agent, a custom CA certificate, or a specific library.

In this final part of our series, we will cover the two strategies for customizing DHI: the Docker Hub UI (for platform teams creating “Golden Images”) and the multi-stage build pattern (for developers building applications).

Option 1: The Golden Image (Docker Hub UI)

If you are a Platform or DevOps Engineer, your goal is likely to provide a “blessed” base image for your internal teams. For example, you might want a standard Node.js image that always includes your corporate root CA certificate and your security logging agent.The Docker Hub UI is the preferred path for this. The strongest argument for using the Hub UI is maintenance automation.

The Killer Feature: Automatic Rebuilds

When you customize an image via the UI, Docker understands the relationship between your custom layers and the hardened base. If Docker releases a patch for the underlying DHI base image (e.g., a fix in glibc or openssl), Docker Hub automatically rebuilds your custom image.

You don’t need to trigger a CI pipeline. You don’t need to monitor CVE feeds. The platform handles the patching and rebuilding, ensuring your “Golden Image” is always compliant with the latest security standards.

How It Works

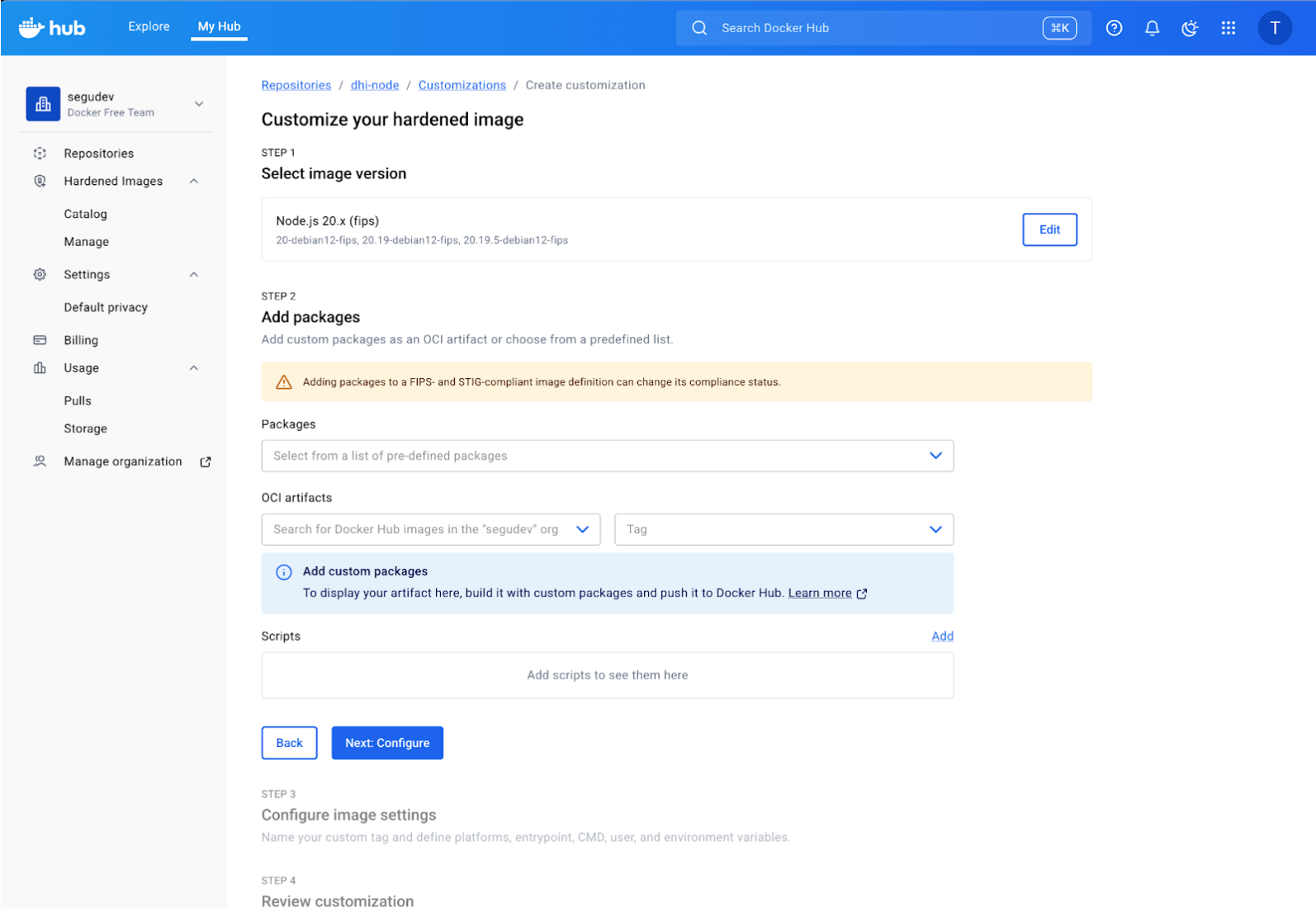

Since you have an Organization setup for this trial, you can explore this directly in Docker Hub.First, navigate to Repositories in your organization dashboard. Locate the image you want to customize (e.g., dhi-node), then the Customizations tab and click the “Create customization” action. This initiates a customization workflow as follows:

In the “Add packages” section, you can search for and select OS packages directly from the distribution’s repository. For example, here we are adding bash to the image for debugging purposes. You can also add “OCI Artifacts” to inject custom files like certificates or agents.

Finally, configure the runtime settings (User, Environment Variables) and review your build. Docker Hub will verify the configuration and queue the build. Once complete, this image will be available in your organization’s private registry and will automatically rebuild whenever the base DHI image is updated.

This option is best suited for creating standardized “golden” base images that are used across the entire organization. The primary advantage is zero-maintenance security patching due to automatic rebuilds by Docker Hub. However, it is less flexible for rapid, application-specific iteration by individual development teams.

Option 2: Multi-Stage Build

If you are an developper, you likely define your environment in a Dockerfile that lives alongside your code. You need flexibility, and you need it to work locally on your machine.

Since DHI images don’t have apt-get or curl, you cannot simply RUN apt-get install my-lib in your Dockerfile. It will fail.

Instead, we use the multi-stage build pattern. The concept is simple:

Stage 1 (Builder): Use a standard “fat” image (like debian:bookworm-slim) to download, compile, and prepare your dependencies.

Stage 2 (Runtime): Copy only the resulting artifacts into the pristine DHI base.

This keeps your final image minimal, non-root, and secure, while still allowing you to install whatever you need.

Hands-on Tutorial: Adding a Monitoring Agent

Let’s try this locally. We will simulate a common real-world scenario: adding the Datadog APM library (dd-trace) globally to a Node.js DHI image.

1. Setup

Create a new directory for this test and add a simple server.js file. This script attempts to load the dd-trace library to verify our installation.

app/server.js

// Simple Express server to demonstrate DHI customization

console.log('Node.js version:', process.version);

try {

require('dd-trace');

console.log('dd-trace module loaded successfully!');

} catch (e) {

console.error('Failed to load dd-trace:', e.message);

process.exit(1);

}

console.log('Running as UID:', process.getuid(), 'GID:', process.getgid());

console.log('DHI customization test successful!');

2. Hardened Dockerfile

Now, create the Dockerfile. We will use a standard Debian image to install the library, and then copy it to our DHI Node.js image. Create a new directory for this test and add a simple server.js file. This script attempts to load the dd-trace library to verify our installation.

# Stage 1: Builder – a standard Debian Slim image that has apt, curl, and full shell access.

FROM debian:bookworm-slim AS builder

# Install Node.js (matching our target version) and tools

RUN apt-get update &&

apt-get install -y curl &&

curl -fsSL https://deb.nodesource.com/setup_24.x | bash – &&

apt-get install -y nodejs

# Install Datadog APM agent globally (we force the install prefix to /usr/local so we know exactly where files go)

RUN npm config set prefix /usr/local &&

npm install -g dd-trace@5.0.0

# Stage 2: Runtime – we switch to the Docker Hardened Image.

FROM <your-org-namespace>/dhi-node:24.11-debian13-fips

# Copy only the required library from the builder stage

COPY –from=builder /usr/local/lib/node_modules/dd-trace /usr/local/lib/node_modules/dd-trace

# Environment Configuration

# DHI images are strict. We must explicitly tell Node where to find global modules.

ENV NODE_PATH=/usr/local/lib/node_modules

# Copy application code

COPY app/ /app/

WORKDIR /app

# DHI Best Practice: Use the exec form (["node", …])

# because there is no shell to process strings.

CMD ["node", "server.js"]

3. Build and Run

Build the custom image:

docker build -t dhi-monitoring-test .

Now run it. If successful, the container should start, find the library, and exit cleanly.

docker run –rm dhi-monitoring-test

Output:

Node.js version: v24.11.0

dd-trace module loaded successfully!

Running as UID: 1000 GID: 1000

DHI customization test successful!

Success! We have a working application with a custom global library, running on a hardened, non-root base.

Security Check

We successfully customized the image. But did we compromise its security?

This is the most critical lesson of operationalizing DHI: hardened base images protect the OS, but they do not protect you from the code you add.Let’s verify our new image with Docker Scout.

docker scout cves dhi-monitoring-test –only-severity critical,high

Sample Output:

✗ Detected 1 vulnerable package with 1 vulnerability

…

0C 1H 0M 0L lodash.pick 4.4.0

pkg:npm/lodash.pick@4.4.0

✗ HIGH CVE-2020-8203 [Improperly Controlled Modification of Object Prototype Attributes]

This result is accurate and important. The base image (OS, OpenSSL, Node.js runtime) is still secure. However, the dd-trace library we just installed pulled in a dependency (lodash.pick) that contains a High severity vulnerability.

This proves that your verification pipeline works.

If we hadn’t scanned the custom image, we might have assumed we were safe because we used a “Hardened Image.” By using Docker Scout on the final artifact, we caught a supply chain vulnerability introduced by our customization.

Let’s check how much “bloat” we added compared to the clean base.

docker scout compare –to <your-org-namespace>/dhi-node:24.11-debian13-fips dhi-monitoring-test

You will see that the only added size corresponds to the dd-trace library (~5MB) and our application code. We didn’t accidentally inherit apt, curl, or the build caches from the builder stage. The attack surface remains minimized.

A Note on Provenance: Who Signs What?

In Part 2, we verified the SLSA Provenance and cryptographic signatures of Docker Hardened Images. This is crucial for establishing a trusted supply chain. When you customize an image, the question of who “owns” the signature becomes important.

Docker Hub UI Customization: When you customize an image through the Docker Hub UI, Docker itself acts as the builder for your custom image. This means the resulting customized image inherits signed provenance and attestations directly from Docker’s build infrastructure. If the base DHI receives a security patch, Docker automatically rebuilds and re-signs your custom image, ensuring continuous trust. This is a significant advantage for platform teams creating “golden images.”

Local Dockerfile: When you build a custom image using a multi-stage Dockerfile locally (as we did in our tutorial), you are the builder. Your docker build command produces a new image with a new digest. Consequently, the original DHI signature from Docker does not apply to your final custom image (because the bits have changed and you are the new builder).However, the chain of trust is not entirely broken:

Base Layers: The underlying DHI layers within your custom image still retain their original Docker attestations.

Custom Layer: Your organization is now the “builder” of the new layers.

For production deployments using the multi-stage build, you should integrate Cosign or Docker Content Trust into your CI/CD pipeline to sign your custom images. This closes the loop, allowing you to enforce policies like: “Only run images built by MyOrg, which are based on verified DHI images and have our internal signature.”

Measuring Your ROI: Questions for Your Team

As you conclude your Docker Hardened Images trial, it’s critical to quantify the value for your organization. Reflect on the concrete results from your migration and customization efforts using these questions:

Vulnerability Reduction: How significantly did DHI impact your CVE counts? Compare the “before and after” vulnerability reports for your migrated services. What is the estimated security risk reduction?

Engineering Effort: What was the actual engineering effort required to migrate an image to DHI? Consider the time saved on patching, vulnerability triage, and security reviews compared to managing traditional base images.

Workflow: How well does DHI integrate into your team’s existing development and CI/CD workflows? Do developers find the customization patterns (Golden Image / Builder Pattern) practical and efficient? Is your team likely to adopt this long-term?

Compliance & Audit: Has DHI simplified your compliance reporting or audit processes due to its SLSA provenance and FIPS compliance? What is the impact on your regulatory burden?

Conclusion

Thanks for following through to the end! Over this 3-part blog series, you have moved from a simple trial to a fully operational workflow:

Migration: You replaced a standard base image with DHI and saw immediate vulnerability reduction.

Verification: You independently validated signatures, FIPS compliance, and SBOMs.

Customization: You learned to extend DHI using the Hub UI (for auto-patching) or multi-stage builds, while checking for new vulnerabilities introduced by your own dependencies.

The lesson here is that the “Hardened” in Docker Hardened Images isn’t a magic shield but a clean foundation. By building on top of it, you ensure that your team spends time securing your application code, rather than fighting a never-ending battle against thousands of upstream vulnerabilities.

Quelle: https://blog.docker.com/feed/