How to add MCP Servers to OpenAI’s Codex with Docker MCP Toolkit

AI assistants are changing how we write code, but their true power is unleashed when they can interact with specialized, high-precision tools. OpenAI’s Codex is a formidable coding partner, but what happens when you connect it directly to your running infrastructure?

Enter the Docker MCP Toolkit.

The Model Context Protocol (MCP) Toolkit acts as a secure bridge, allowing AI models like Codex to safely discover and use any of the 200+ MCP servers from the trusted MCP catalog curated by Docker.

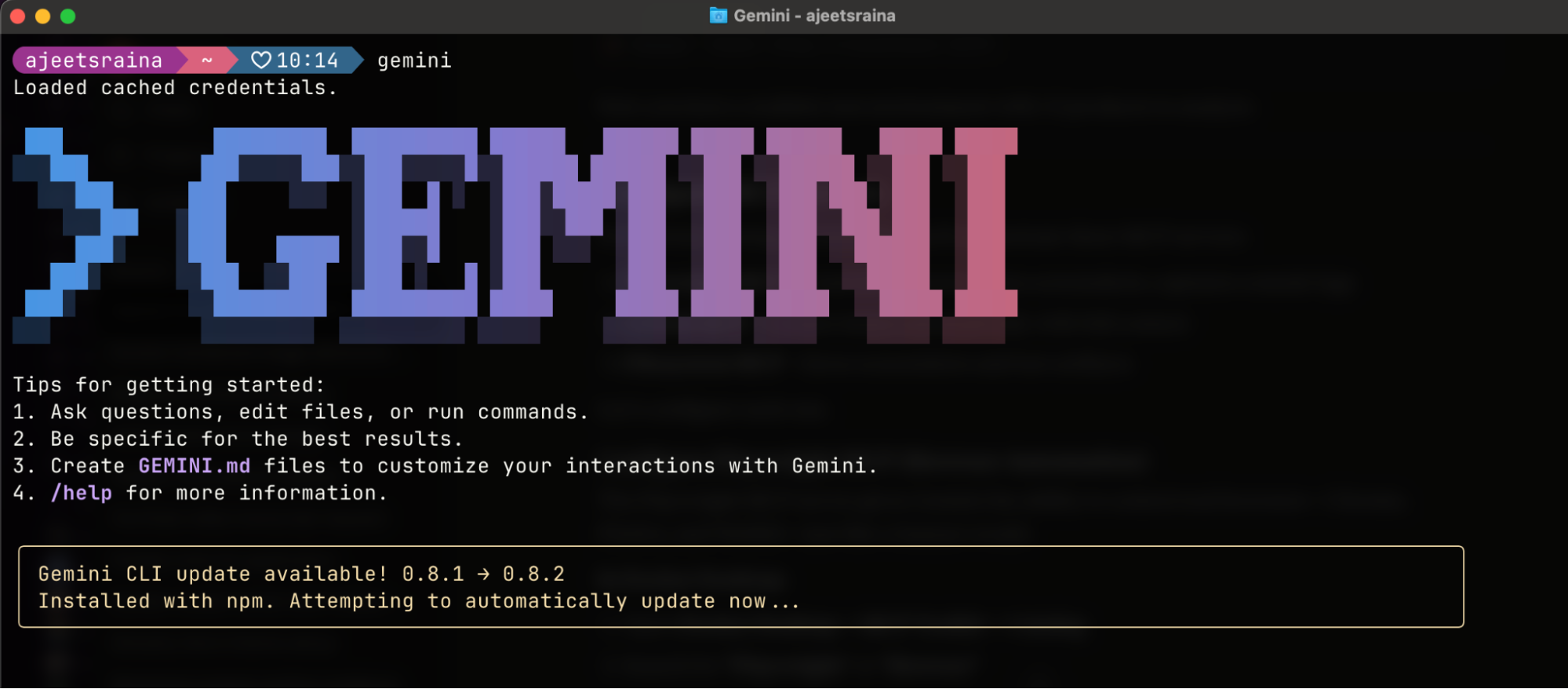

In this post, we’ll walk through an end-to-end demo, just like our Claude Code and Gemini CLI tutorials. But this time, we’re pairing Codex with Neo4j MCP servers.

First, we’ll connect Codex to the Neo4j server using the MCP Toolkit. Then, we’ll show a fun example: building a graph of Pokémon species and their types, and exploring the data visually. While playful, this example highlights how Codex + MCP can be applied to real-world, semi-structured data pipelines.

Read on to see how a generic AI assistant, when supercharged with Docker and MCP, can evolve into a specialized data engineering powerhouse!

Why use Codex with Docker MCP

While Codex provides powerful AI capabilities and MCP provides the protocol, Docker MCP Toolkit makes automated data modeling and graph engineering practical. Without containerization, building a knowledge graph means managing local Neo4j installations, dealing with database driver versions, writing boilerplate connection and authentication code, and manually scripting the entire data validation and loading pipeline. A setup that should take minutes can easily stretch into hours for each developer.

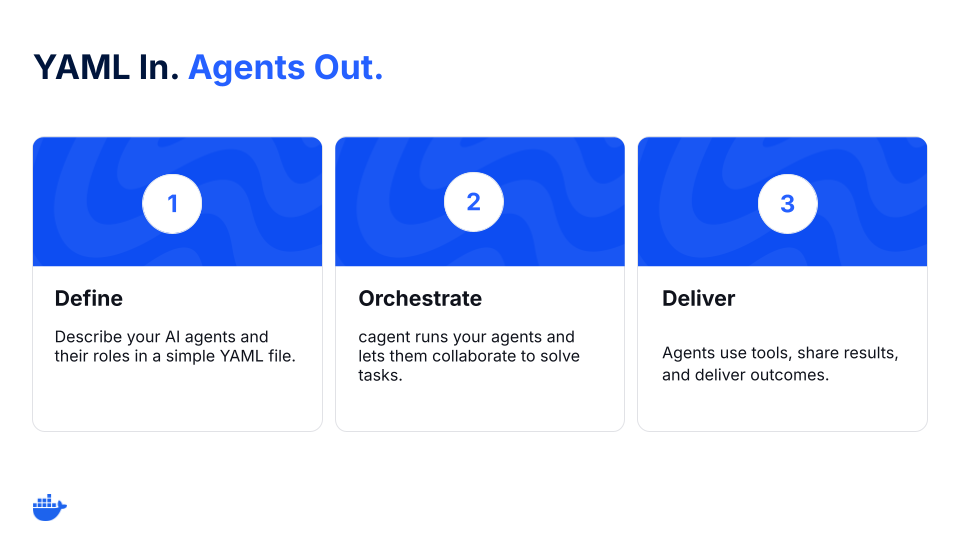

Docker MCP Toolkit eliminates this friction:

200+ pre-built MCP servers in the Catalog

One-click deployment through Docker Desktop

Neo4j Data Modeling MCP for schema design and validation

Neo4j Cypher MCP for direct database queries and ingestion

Secure credential management for database passwords

Consistent configuration across Mac, Windows, and Linux

Automatic updates when new server versions are released

We built Docker MCP Toolkit to meet developers where they are. If you’re using Codex, you should be able to engineer a knowledge graph without wrestling with database infrastructure.

The Setup: Connecting Codex to Neo4j Tools

Prerequisites

First, we need to give Codex access to the specialized Neo4j tools.

Install Codex and run it at least once to get authentication out of the way

Install Docker Desktop 4.40 or later

Enable MCP Toolkit

Step 1: Add the Neo4j MCP Servers

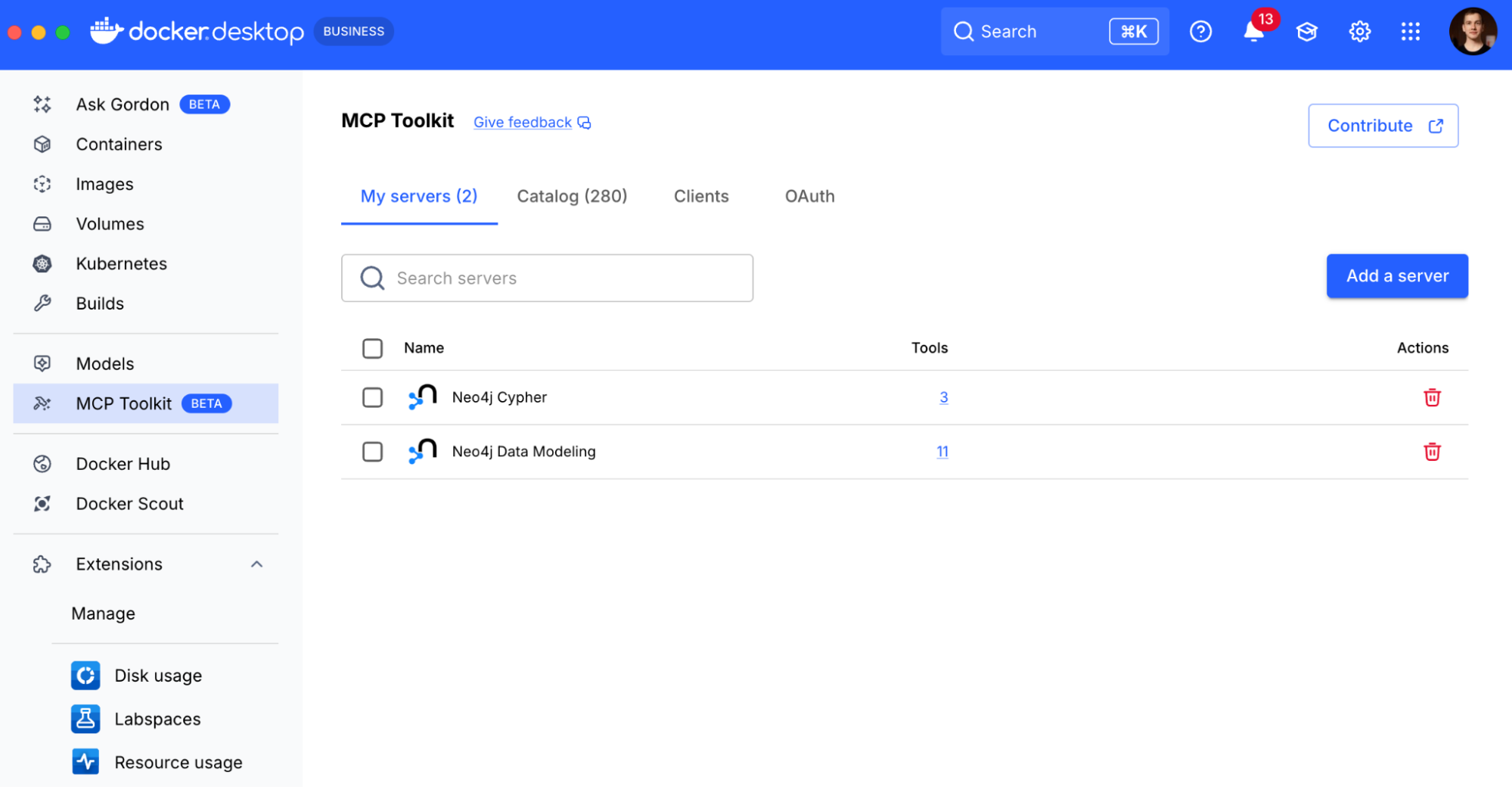

The Neo4j Cypher and Data Modeling servers are available out-of-the-box in the main MCP Toolkit catalog.

In Docker Desktop, navigate to the MCP Toolkit tab.

Click the Catalog tab.

Search for “Neo4j” and click + Add for both the Neo4j Cypher and Neo4j Data Modeling servers.

They will now appear in your “My servers” list.

Step 2: Connect Codex to the MCP Toolkit

With our tools ready, we run a one-time command to make Codex aware of the MCP Toolkit:

docker mcp-client configure codex

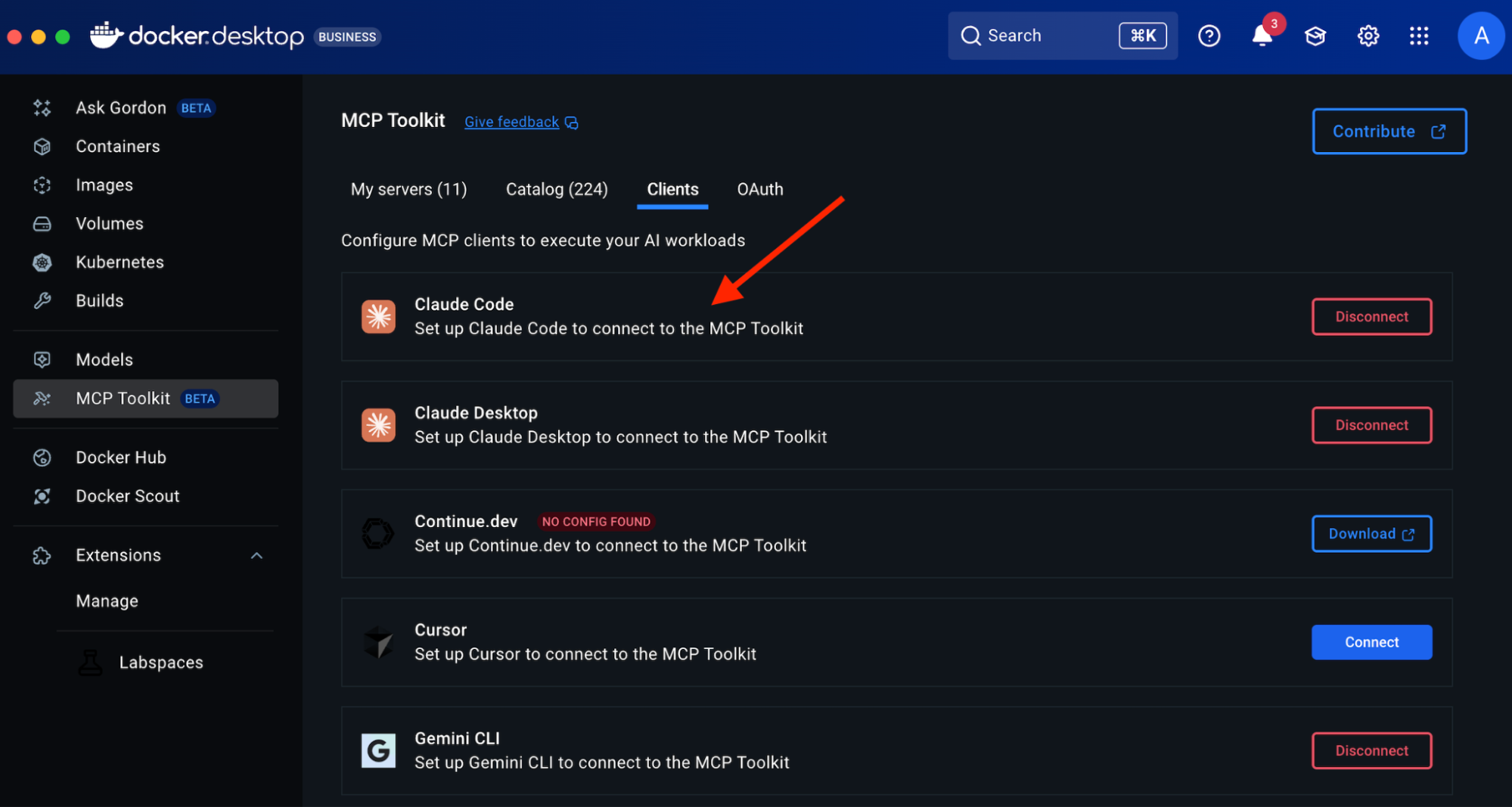

We can also do that from the Docker Desktop UI, navigate to the clients tab, and smash that connect button next to Codex and any other assistants you use:

Docker will edit the corresponding configuration files and next time Codex starts, it’ll connect to the MCP toolkit and you’ll have the tools at your disposal!

Step 3: Start and Configure Neo4j

We still need to configure the Neo4j Cypher MCP server to connect to the Neo4j database, so we’ll set this up now. We’ll use Codex to start our Neo4j database and configure the connection. First, we ask Codex to create the container:

› Spin up a Neo4j container for me in Docker please.

Codex will run the necessary Docker command, and get our Neo4j container running. You can of course do this manually, use a cloud service, or download the Neo4j Desktop application, but since we’re having fun in Codex – then why not make it do these mundane things for us.

With Neo4j available in the container we now need to configure the Neo4j Cypher MCP server to connect to it. The Neo4j Data Modeling MCP server works without any configuration. To simplify you can take a screenshot of the configuration form and ask Codex for the information on how to fill it to connect to the container we just started.

Next, we asked Codex for help, pointing it to a screenshot of the configuration page:

› There is a screenshot in this directory. It has the information we need to configure, MCP server to connect to the Neo4j database. Please look at it and give me the information to configure the MCP server to connect to our Neo4j container.

Codex inspected the container, found the running container, and determined its authentication details (e.g., NEO4J_AUTH=neo4j/password). It then provided the correct configuration values. We just need to update the Neo4j Cypher MCP server configuration in the Docker Desktop UI with the neo4j-cypher.url (neo4j://localhost:7687) and the password.

Fill the form in the Docker MCP toolkit for the Neo4j Cypher MCP server and restart codex now.

Use Case: Building a Pokémon Graph with Codex + Neo4j

Now we’re ready to tackle our original problem of building the graph of Pokémon species. First of all, enter the YOLO mode by typing /approvals and selecting the mode where it has freedom to do whatever it pleases:

Next, we can throw the full power of Codex models at our task. We give it the full problem statement:

› Here's the page with all pokemon in generation 1: https://bulbapedia.bulbagarden.net/wiki/List_of_Pok%C3%A9mon_by_index_number_in_Generation_I

and here's the types information: https://bulbapedia.bulbagarden.net/wiki/Type

we're going to create a graph with data about these pokemon (ignore MissingNo entries – they are a glitch and ignore other glitched pokemon).

you have a neo4j container running, and the MCP tools for modelling and cypher.

Codex will accept the task, break it down into a plan, and start cranking at it.

There are a few interesting moments in how it approaches it, though it largely depends on the model you configure Codex with. For me it was “model: gpt-5-codex” and it tends to use scripting more than chaining curl commands for example.

Here’s the plan you might see if you’re following along:

• I’m preparing to build a Pokemon graph by fetching data from a website using network access. Since this is a complex task, I’ll create a detailed plan involving data gathering, modeling

entities like Pokémon and Types, defining relationships such as evolutions and type effectiveness, and then using tools like MCP Docker to build the Neo4j graph. The first step is to draft

• Updated Plan

└ □ Inspect requirements and gather Generation I Pokémon data with types and evolution chains

□ Define Neo4j graph data model for Pokémon, Types, and relationships

□ Load data into Neo4j via Cypher ingestion and validate

Then it immediately started cranking python scripts with requests, BeautifulSoup and other web scraping friends to fetch the data from the provided wiki. It’s interesting that the Pokemon data is not actually on a single page, but spread through subpages for every Pokemon species, so perhaps scraping with Python makes a ton of sense over curling the pages and spending tokens on processing the data in the model. And it leaves the scripts behind so you can verify and reproduce the results if needed.

Eventually the model proceeds to analyze the data, and here the MCP tools become really helpful. You can see below that it’s calling the MCP_DOCKER.validate_data_model from the server we configured earlier.

I'm outlining a comprehensive data model for Pokemon, types, and their relationships with precise property types and units converted for better clarity. I plan to generate ingestion-ready

JSON files via a Python script to integrate cleanly with Neo4j ingestion tools, ensuring the data pipeline is robust and structured.

└ wrote data model to data/gen1_pokemon_model.json

• Called MCP_DOCKER.validate_data_model({"data_model":"data/gen1_pokemon_model.json","return_validated":true})

└ Input validation error: 'data/gen1_pokemon_model.json' is not of type 'object'

….

It took Codex a few attempts to figure out the data model json schema and produce one for the Pokémon that satisfied the Neo4j Data Modelling MCP server.

Then it returned to Python for creating the data ingestion script and loaded the data into the Neo4j instance.

A few MCP tool calls later to query the data with cypher (query language for graph databases) which it can do because it has access to the MCP server for Neo4j Cypher. And with it, Codex and the MCP servers can answer analytical questions about our data.

– Greedy type-coverage search suggests trios such as (Rhydon, Parasect, Dragonite) or (Rhydon, Parasect, Jynx) hit 13 of the 15 defending types super-effectively; no trio can cover Normal/Rock simultaneously because Normal has no offensive 2× matchup.

Now what’s really fun about Neo4j is that it comes with a terrific console where you can explore the data.

While our Neo4j container with the Pokémon data is still running we can go to http://localhost:7474, enter neo4j/password credentials and get to explore the data in a visual way.

Here for example is a subset of the Pokémon and their type relationships.

And if you know Cypher or have an AI assistant that can generate Cypher queries (and verify they work with an MCP tool call), you can generate more complex projections of your data, for example this (generated by Codex) shows all Pokémon, their evolution relationships and primary/secondary types.

MATCH (p:Pokemon)

CALL {

WITH p

OPTIONAL MATCH (p)-[:EVOLVES_TO*1..]->(evo:Pokemon)

WITH collect(DISTINCT evo) AS evos

RETURN [e IN evos WHERE e IS NOT NULL | {node: e, relType: 'EVOLVES_TO'}] AS evolutionConnections

}

CALL {

WITH p

OPTIONAL MATCH (p)-[:HAS_TYPE]->(type:Type)

WITH type

ORDER BY type.name // ensures a stable primary/secondary ordering

RETURN collect(type) AS orderedTypes

}

WITH p, evolutionConnections, orderedTypes,

CASE WHEN size(orderedTypes) >= 1 THEN orderedTypes[0] END AS primaryType,

CASE WHEN size(orderedTypes) >= 2 THEN orderedTypes[1] END AS secondaryType

WITH p,

evolutionConnections +

CASE WHEN primaryType IS NULL THEN [] ELSE [{node: primaryType, relType: 'HAS_PRIMARY_TYPE'}] END +

CASE WHEN secondaryType IS NULL THEN [] ELSE [{node: secondaryType, relType: 'HAS_SECONDARY_TYPE'}] END AS connections

UNWIND connections AS connection

RETURN p AS pokemon,

connection.node AS related,

connection.relType AS relationship

ORDER BY pokemon.name, relationship, related.name;

Turn Your AI Coding Assistant into a Data Engineer, Architect, Analyst and More

While this Pokémon demo is a fun example, it’s also a practical blueprint for working with real-world, semi-structured data. Graph databases like Neo4j are especially well-suited for this kind of work. Their relationship-first model makes it easier to represent the complexity of real-world systems.

In this walkthrough, we showed how to connect OpenAI’s Codex to the Neo4j MCP Servers via Docker MCP Toolkit, enabling it to take on multiple specialized roles:

Data Engineer: Writing Python to scrape and transform web data

Data Architect: Designing and validating graph models using domain-specific tools

DevOps Engineer: Starting services and configuring tools based on its environment

Data Analyst: Running complex Cypher and Python queries to extract insights

In your own projects, you might ask your AI assistant to “Analyze production logs and identify the cause of performance spikes,” “Migrate the user database schema to a new microservice,” or “Model our product catalog from a set of messy CSVs.”

Summary

The Docker MCP Toolkit bridges the gap between powerful AI coding agents and the specialized tools they need to be truly useful. By providing secure, one-click access to a curated catalog of over 200 MCP servers, it enables AI agents to interact with real infrastructure, including databases, APIs, command-line tools, and more. Whether you’re automating data workflows, querying complex systems, or orchestrating services, the MCP Toolkit equips your assistant to work like a real developer. If you’re building with AI coding assistants and want it to go beyond code generation, it’s time to start integrating with the tools your stack already relies on!

Learn more

Explore the MCP Catalog: Discover containerized, security-hardened MCP servers

Open Docker Desktop and get started with the MCP Toolkit (Requires version 4.48 or newer to launch the MCP Toolkit automatically)

Read our tutorial on How to Add MCP Servers to Claude Code with Docker MCP Toolkit

Read our tutorial on How to Add MCP Servers to Gemini CLI with Docker MCP Toolkit

Quelle: https://blog.docker.com/feed/