At Docker, we’re incredibly proud of our vibrant, diverse and creative community. From time to time, we feature cool contributions from the community on our blog to highlight some of the great work our community does. Are you working on something awesome with Docker? Send your contributions to Ajeet Singh Raina (@ajeetraina) on the Docker Community Slack and we might feature your work!

Over the last five years, TypeScript’s popularity has surged among enterprise developers. In Stack Overflow’s 2022 Developer Survey, TypeScript ranked third in the “most wanted” category. Stack Overflow reserves this distinction for developers who aren’t developing with a specific language or technology, but have expressed interest in doing so.

Data courtesy of Stack Overflow.

TypeScript’s incremental adoption is attributable to enhancements in developer code quality and comprehensibility. Overall, Typescript encourages developers to thoroughly document their code and inspires greater confidence through ease of use. TypeScript offers every modern JavaScript feature while introducing powerful concepts like interfaces, unions, and intersection types. It improves developer productivity by clearly displaying syntax errors during compilation, rather than letting things fail at runtime.

However, remember that every programming language comes with certain drawbacks, and TypeScript is no exception. Long compilation times and a steeper learning curve for new JavaScript users are most noteworthy.

Building Your Application

In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to build a basic URL shortener from scratch using TypeScript and Nest.

First, you’ll create a basic application in Nest without using Docker. You’ll see how the application lets you build a simple URL shortening service in Nest and TypeScript, with a Redis backend. Next, you’ll learn how Docker Compose can help you jointly run a Nest.js, TypeScript, and Redis backend to power microservices. Let’s jump in.

Getting Started

The following key components are essential to completing this walkthrough:

Node.js

NPM

VS Code

Docker Desktop

Before starting, make sure you have Node installed on your system. Then, follow these steps to build a simple web application with TypeScript.

Creating a Nest Project

Nest is currently the fastest growing server-side development framework in the JavaScript ecosystem. It’s ideal for writing scalable, testable, and loosely-coupled applications. Nest provides a level of abstraction above common Node.js frameworks and exposes their APIs to the developer. Under the hood, Nest makes use of robust HTTP server frameworks like Express (the default) and can optionally use Fastify as well! It supports databases like PostgreSQL, MongoDB, and MySQL. NestJS is heavily influenced by Angular, React, and Vue — while offering dependency injection right out of the box.

For first-time users, we recommend creating a new project with the Nest CLI. First, enter the following command to install the Nest CLI.

npm install -g @nestjs/cli

Next, let’s create a new Nest.js project directory called backend.

mkdir backend

It’s time to populate the directory with the initial core Nest files and supporting modules. From your new backend directory, run Nest’s bootstrapping command. We’ll call our new application link-shortener:

nest new link-shortener

⚡ We will scaffold your app in a few seconds..

CREATE link-shortener/.eslintrc.js (665 bytes)

CREATE link-shortener/.prettierrc (51 bytes)

CREATE link-shortener/README.md (3340 bytes)

CREATE link-shortener/nest-cli.json (118 bytes)

CREATE link-shortener/package.json (1999 bytes)

CREATE link-shortener/tsconfig.build.json (97 bytes)

CREATE link-shortener/tsconfig.json (546 bytes)

CREATE link-shortener/src/app.controller.spec.ts (617 bytes)

CREATE link-shortener/src/app.controller.ts (274 bytes)

CREATE link-shortener/src/app.module.ts (249 bytes)

CREATE link-shortener/src/app.service.ts (142 bytes)

CREATE link-shortener/src/main.ts (208 bytes)

CREATE link-shortener/test/app.e2e-spec.ts (630 bytes)

CREATE link-shortener/test/jest-e2e.json (183 bytes)

? Which package manager would you ❤️ to use? (Use arrow keys)

❯ npm

yarn

pnpm

All three packages managers are usable, but we’ll choose npm for the purposes of this walkthrough.

Which package manager would you ❤️ to use? npm

✔ Installation in progress… ☕

🚀 Successfully created project link-shortener

👉 Get started with the following commands:

$ cd link-shortener

$ npm run start

Thanks for installing Nest 🙏

Please consider donating to our open collective

to help us maintain this package.

🍷 Donate: https://opencollective.com/nest</pre>

Once the command is executed successfully, it creates a new link-shortener project directory with node modules and a few other boilerplate files. It also creates a new src/ directory populated with several core files as shown in the following directory structure:

tree -L 2 -a

.

└── link-shortener

├── dist

├── .eslintrc.js

├── .gitignore

├── nest-cli.json

├── node_modules

├── package.json

├── package-lock.json

├── .prettierrc

├── README.md

├── src

├── test

├── tsconfig.build.json

└── tsconfig.json

5 directories, 9 files

Let’s look at the core files ending with .ts (TypeScript) under /src directory:

src % tree

.

├── app.controller.spec.ts

├── app.controller.ts

├── app.module.ts

├── app.service.ts

└── main.ts

0 directories, 5 files

Nest embraces modularity. Accordingly, two of the most important Nest app components are controllers and providers. Controllers determine how you handle incoming requests. They’re responsible for accepting incoming requests, performing some kind of operation, and returning the response. Meanwhile, providers are extra classes which you can inject into the controllers or to certain providers. This grants various supplemental functionality. We always recommend reading up on providers and controllers to better understand how they work.

The app.module.ts is the root module of the application and bundles up a couple of controllers and providers that the controller uses.

cat app.module.ts

import { Module } from ‘@nestjs/common';

import { AppController } from ‘./app.controller';

import { AppService } from ‘./app.service';

@Module({

imports: [],

controllers: [AppController],

providers: [AppService],

})

export class AppModule {}

As shown in the above file, AppModule is just an empty class. Nest’s @Module decorator is responsible for providing the config that lets Nest build a functional application from it.

First, app.controller.ts exports a basic controller with a single route. The app.controller.spec.ts is the unit test for the controller. Second, app.service.ts is a basic service with a single method. Third, main.ts is the entry file of the application. It bootstraps the application by calling NestFactory.create, then starts the new application by having it listen for inbound HTTP requests on port 3000.

import { NestFactory } from ‘@nestjs/core';

import { AppModule } from ‘./app.module';

async function bootstrap() {

const app = await NestFactory.create(AppModule);

await app.listen(3000);

}

bootstrap();

Running the Application

Once the installation is completed, run the following command to start your application:

npm run start

> link-shortener@0.0.1 start

> nest start

[Nest] 68686 – 05/31/2022, 5:50:59 PM LOG [NestFactory] Starting Nest application…

[Nest] 68686 – 05/31/2022, 5:50:59 PM LOG [InstanceLoader] AppModule dependencies initialized +24ms

[Nest] 68686 – 05/31/2022, 5:50:59 PM LOG [RoutesResolver] AppController {/}: +4ms

[Nest] 68686 – 05/31/2022, 5:50:59 PM LOG [RouterExplorer] Mapped {/, GET} route +2ms

[Nest] 68686 – 05/31/2022, 5:50:59 PM LOG [NestApplication] Nest application successfully started +1ms

This command starts the app with the HTTP server listening on the port defined in the src/main.ts file. Once the application is successfully running, open your browser and navigate to http://localhost:3000. You should see the “Hello World!” message:

Let’s now add a new test for our new endpoint in app.service.spec.ts:

import { Test, TestingModule } from "@nestjs/testing";

import { AppService } from "./app.service";

import { AppRepositoryTag } from "./app.repository";

import { AppRepositoryHashmap } from "./app.repository.hashmap";

import { mergeMap, tap } from "rxjs";

describe(‘AppService’, () => {

let appService: AppService;

beforeEach(async () => {

const app: TestingModule = await Test.createTestingModule({

providers: [

{ provide: AppRepositoryTag, useClass: AppRepositoryHashmap },

AppService,

],

}).compile();

appService = app.get<AppService>(AppService);

});

describe(‘retrieve’, () => {

it(‘should retrieve the saved URL’, done => {

const url = ‘docker.com';

appService.shorten(url)

.pipe(mergeMap(hash => appService.retrieve(hash)))

.pipe(tap(retrieved => expect(retrieved).toEqual(url)))

.subscribe({ complete: done })

});

});

});

Before running our tests, let’s implement the function in app.service.ts:

import { Inject, Injectable } from ‘@nestjs/common';

import { map, Observable } from ‘rxjs';

import { AppRepository, AppRepositoryTag } from ‘./app.repository';

@Injectable()

export class AppService {

constructor(

@Inject(AppRepositoryTag) private readonly appRepository: AppRepository,

) {}

getHello(): string {

return ‘Hello World!';

}

shorten(url: string): Observable<string> {

const hash = Math.random().toString(36).slice(7);

return this.appRepository.put(hash, url).pipe(map(() =>; hash)); // <– here

}

retrieve(hash: string): Observable<string> {

return this.appRepository.get(hash); // <– and here

}

}

Run these tests once more to confirm that everything passes, before we begin storing the data in a real database.

Add a Database

So far, we’re just storing our mappings in memory. That’s fine for testing, but we’ll need to store them somewhere more centralized and durable in production. We’ll use Redis, a popular key-value store available on Docker Hub.

Let’s install this Redis client by running the following command from the backend/link-shortener directory:

npm install redis@4.1.0 –save

Inside /src, create a new version of the AppRepository interface that uses Redis. We’ll call this file app.repository.redis.ts:

import { AppRepository } from ‘./app.repository';

import { Observable, from, mergeMap } from ‘rxjs';

import { createClient, RedisClientType } from ‘redis';

export class AppRepositoryRedis implements AppRepository {

private readonly redisClient: RedisClientType;

constructor() {

const host = process.env.REDIS_HOST || ‘redis';

const port = +process.env.REDIS_PORT || 6379;

this.redisClient = createClient({

url: `redis://${host}:${port}`,

});

from(this.redisClient.connect()).subscribe({ error: console.error });

this.redisClient.on(‘connect’, () => console.log(‘Redis connected’));

this.redisClient.on(‘error’, console.error);

}

get(hash: string): Observable<string&> {

return from(this.redisClient.get(hash));

}

put(hash: string, url: string): Observable<string> {

return from(this.redisClient.set(hash, url)).pipe(

mergeMap(() => from(this.redisClient.get(hash))),

);

}

}

Finally, it’s time to change the provider in app.module.ts to our new Redis repository from the in-memory version:

import { Module } from ‘@nestjs/common';

import { AppController } from ‘./app.controller';

import { AppService } from ‘./app.service';

import { AppRepositoryTag } from ‘./app.repository';

import { AppRepositoryRedis } from "./app.repository.redis";

@Module({

imports: [],

controllers: [AppController],

providers: [

AppService,

{ provide: AppRepositoryTag, useClass: AppRepositoryRedis }, // <– here

],

})

export class AppModule {}

Finalize the Backend

Head back to app.controller.ts and create another endpoint for redirect:

import { Body, Controller, Get, Param, Post, Redirect } from ‘@nestjs/common';

import { AppService } from ‘./app.service';

import { map, Observable, of } from ‘rxjs';

interface ShortenResponse {

hash: string;

}

interface ErrorResponse {

error: string;

code: number;

}

@Controller()

export class AppController {

constructor(private readonly appService: AppService) {}

@Get()

getHello(): string {

return this.appService.getHello();

}

@Post(‘shorten’)

shorten(@Body(‘url’) url: string): Observable<ShortenResponse | ErrorResponse> {

if (!url) {

return of({ error: `No url provided. Please provide in the body. E.g. {‘url':’https://google.com’}`, code: 400 });

}

return this.appService.shorten(url).pipe(map(hash => ({ hash })));

}

@Get(‘:hash’)

@Redirect()

retrieveAndRedirect(@Param(‘hash’) hash): Observable<{ url: string }> {

return this.appService.retrieve(hash).pipe(map(url => ({ url })));

}

}

Click here to access the code previously developed for this example.

Containerizing the TypeScript Application

Docker helps you containerize your TypeScript app, letting you bundle together your complete TypeScript application, runtime, configuration, and OS-level dependencies. This includes everything needed to ship a cross-platform, multi-architecture web application.

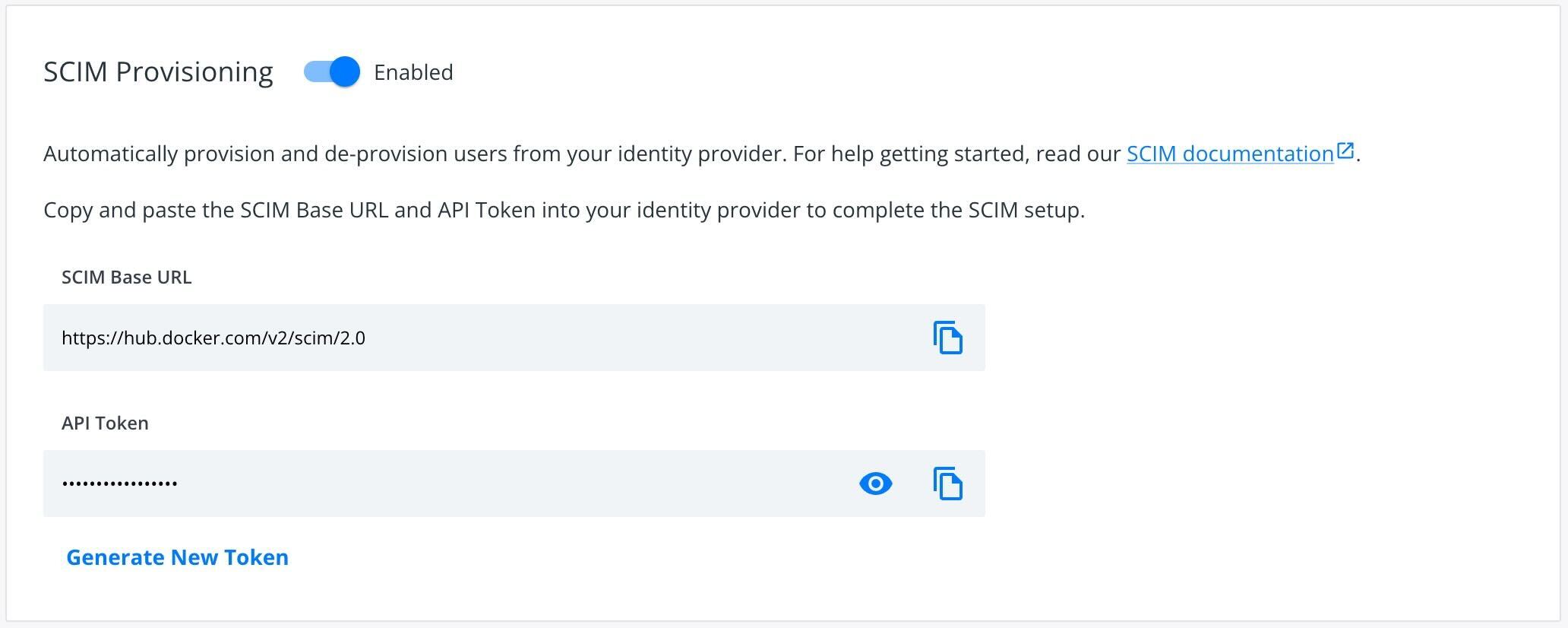

Let’s see how you can easily run this app inside a Docker container using a Docker Official Image. First, you’ll need to download Docker Desktop. Docker Desktop accelerates the image-building process while making useful images more discoverable. Complete the installation process once your download is finished.

Docker uses a Dockerfile to specify an image’s “layers.” Each layer stores important changes building upon the base image’s standard configuration. Create the following empty Dockerfile in your Nest project.

touch Dockerfile

Use your favorite text editor to open this Dockerfile. You’ll then need to define your base image. Let’s also quickly create a directory to house our image’s application code. This acts as the working directory for your application:

WORKDIR /app

The following COPY instruction copies the files from the host machine to the container image:

COPY . .

Finally, this closing line tells Docker to compile and run your application packages:

CMD[“npm”, “run”, “start:dev”]

Here’s your complete Dockerfile:

FROM node:16

COPY . .

WORKDIR /app

RUN npm install

EXPOSE 3000

CMD ["npm", "run", "start:dev"]

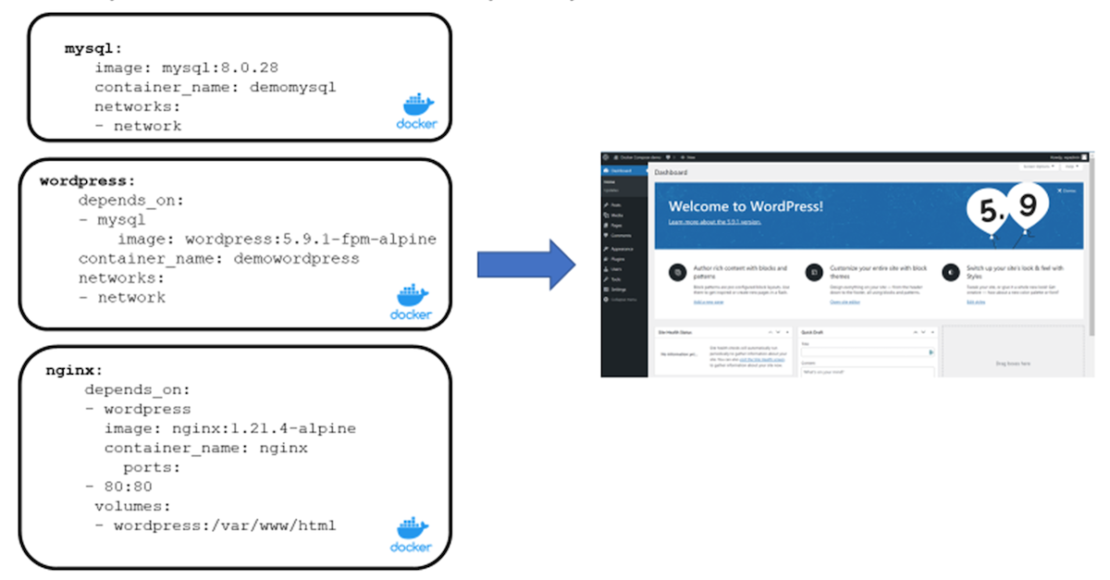

You’ve effectively learned how to build a Dockerfile for a sample TypeScript app. Next, let’s see how to create an associated Docker Compose file for this application. Docker Compose is a tool for defining and running multi-container Docker applications. With Compose, you’ll use a YAML file to configure your services. Then, with a single command, you can create and start every service from your configuration.

Defining Services Using a Compose File

It’s time to define your services in a Docker Compose file:

services:

redis:

image: ‘redis/redis-stack’

ports:

– ‘6379:6379′

– ‘8001:8001′

networks:

– urlnet

dev:

build:

context: ./backend/link-shortener

dockerfile: Dockerfile

environment:

REDIS_HOST: redis

REDIS_PORT: 6379

ports:

– ‘3000:3000′

volumes:

– ‘./backend/link-shortener:/app’

depends_on:

– redis

networks:

– urlnet

networks:

urlnet:

Your example application has the following parts:

Two services backed by Docker images: your frontend dev app and your backend database redis

The redis/redis-stack Docker image is an extension of Redis that adds modern data models and processing engines to provide a complete developer experience. We use port 8001 for RedisInsight — a visualization tool for understanding and optimizing Redis data.

The frontend, accessible via port 3000

The depends_on parameter, letting you create your backend service before the frontend service starts

One persistent volume, attached to the backend

The environmental variables for your Redis database

Once you’ve stopped the frontend and backend services that we ran in the previous section, let’s build and start our services using the docker-compose up command:

docker compose up -d –build

Note: If you’re using Docker Compose v1, the command line syntax is docker-compose with a hyphen. If you’re using v2, which ships with Docker Desktop, the hyphen is omitted and docker compose is correct.

docker compose ps

NAME COMMAND SERVICE STATUS PORTS

link-shortener-js-dev-1 "docker-entrypoint.s…" dev running 0.0.0.0:3000->3000/tcp

link-shortener-js-redis-1 "/entrypoint.sh" redis running 0.0.0.0:6379->6379/tcp, 0.0.0.0:8001->8001/tcp

Just like that, you’ve created and deployed your TypeScript URL shortener! You can use this in your browser like before. If you visit the application at https://localhost:3000, you should see a friendly “Hello World!” message. Use the following curl command to shorten a new link:

curl -XPOST -d "url=https://docker.com" localhost:3000/shorten

Here’s your response:

{"hash":"l6r71d"}

This hash may differ on your machine. You can use it to redirect to the original link. Open any web browser and visit https://localhost:3000/l6r71d to access Docker’s website.

Viewing the Redis Keys

You can view the Redis keys with the RedisInsight tool by visiting https://localhost:8001.

Viewing the Compose Logs

You can use docker compose logs -f to check and view your Compose logs:

[6:17:19 AM] Starting compilation in watch mode…

link-shortener-js-dev-1 |

link-shortener-js-dev-1 | [6:17:22 AM] Found 0 errors. Watching for file changes.

link-shortener-js-dev-1 |

link-shortener-js-dev-1 | [Nest] 31 – 06/18/2022, 6:17:23 AM LOG [NestFactory] Starting Nest application…

link-shortener-js-dev-1 | [Nest] 31 – 06/18/2022, 6:17:23 AM LOG [InstanceLoader] AppModule dependencies initialized +21ms

link-shortener-js-dev-1 | [Nest] 31 – 06/18/2022, 6:17:23 AM LOG [RoutesResolver] AppController {/}: +3ms

link-shortener-js-dev-1 | [Nest] 31 – 06/18/2022, 6:17:23 AM LOG [RouterExplorer] Mapped {/, GET} route +1ms

link-shortener-js-dev-1 | [Nest] 31 – 06/18/2022, 6:17:23 AM LOG [RouterExplorer] Mapped {/shorten, POST} route +0ms

link-shortener-js-dev-1 | [Nest] 31 – 06/18/2022, 6:17:23 AM LOG [RouterExplorer] Mapped {/:hash, GET} route +1ms

link-shortener-js-dev-1 | [Nest] 31 – 06/18/2022, 6:17:23 AM LOG [NestApplication] Nest application successfully started +1ms

link-shortener-js-dev-1 | Redis connected

You can also leverage the Docker Dashboard to view your container’s ID and easily access or manage your application:

You can also inspect important logs via the Docker Dashboard:

Conclusion

Congratulations! You’ve successfully learned how to build and deploy a URL shortener with TypeScript and Nest. Using a single YAML file, we demonstrated how Docker Compose helps you easily build and deploy a TypeScript-based URL shortener app in seconds. With just a few extra steps, you can apply this tutorial while building applications with much greater complexity.

Happy coding.

Quelle: https://blog.docker.com/feed/