This Conservative Mom And Liberal Daughter Were Surprised By How Different Their Facebook Feeds Are

Lixia Guo & Lam Thuy Vo / BuzzFeed News

Katherine Cooper, 60, and Lindsey Linder, 28, are very similar. They’re mother and daughter and both grew up in West Monroe, La., a town of a little less than 13,000 people located four hours north of New Orleans. They both spend their working hours helping others — Lindsey as a policy attorney for the Texas Justice Coalition, a group advocating for criminal justice reform, and Katherine as a caregiver and teacher.

But like many American families in recent months, they have gotten caught up in vehement disagreements about the US election, its results, and other ideological issues. And not just that. On Facebook, Linder and Cooper’s political differences can lead to heated and ugly spats that both said they would have been able to avoid if they were talking offline.

Last fall, this divide came to a head. At the height of the contentious presidential elections, Linder posted an article titled “White America, It’s Time to Take a Knee” about Colin Kaepernick, an NFL quarterback who garnered national attention last year for refusing to stand during the National anthem at the beginning of his games.

An hour later her mother, Cooper, chimed in. “I love and adore you but Im unfollowing you starting right now,” she wrote as part of a longer comment.

“Go burn flags if thats what you want to do,” her brother added in another comment on the same posted article.

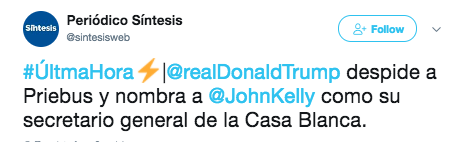

BuzzFeed News

The sparring between Linder and her family and friends from back home became so intense that she temporarily deactivated her Facebook account after the election. Her colleagues in Austin, Texas who had watched Linder’s online disputes were actually worried for her safety when she told them she was going home to visit her family, she said.

“In this political climate it seems that every issue is polarized. There's not a lot of issues that I can say ‘I really care about this’ and it hasn't been made into some kind of dividing factor,” Linder said.

“She's so outspoken cause she would just post anything on Facebook, and we'd be like: ‘What?! Are you kidding?’,” said Cooper about her daughter’s online presence.

“On Facebook for a while [my family and I] were in a very polarized position. […] It just became this place where we could be combative,” said Linder.

One reason why Linder and Cooper disagree so vehemently online may be the fact that the content they see on Facebook hardens beliefs they already have.

Left: A meme from Linder’s timeline. Right: A meme from Cooper’s timeline.

People naturally surround themselves with people who share their beliefs. Online, this self-selected social circle results in people mostly encountering content that confirms rather than questions their beliefs, an effect often referred to as experiencing the world through a “filter bubble.”

To get a better idea about how much Linder and Cooper’s social media worlds differ, BuzzFeed News compared their Facebook news feeds and timelines. They gave us permission to look at a combined total of 2,367 posts shown on their news feeds for one day in January of this year.

The findings of our analysis are very specific to Linder and Cooper but may help illustrate how people’s experience of politics online can aggravate existing political differences and create conflicts that could have been resolved offline in a less contentious manner.

The content they choose to look at

Here are the top 15 pages and groups whose posts showed up most often on Linder and Cooper’s news feeds:

Lam Thuy Vo

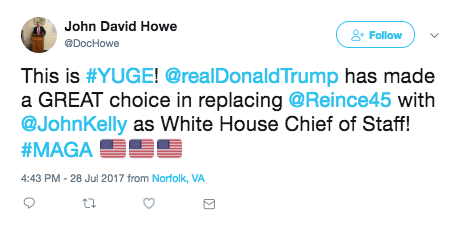

Their interests vary. In terms of politics, for instance, Cooper follows five groups and pages that contain the name “Trump,” including pages with the names “Donald Trump for President,” “Trump & The Great America,” and “Trump Wall.” Cooper also liked one page named “Hillary for Prison.” Linder, on the other hand, receives content from two pages that are related to Bernie Sanders, “U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders” and “Bernie Sanders.” None of the groups mentioned above that Cooper likes are verified by Facebook (meaning the platform has confirmed that the pages are affiliated with the public person they named after), while both pages that Linder follows feature the blue tick mark that signifies them as official Bernie Sanders pages.

Below are two exemplary memes that appeared on Linder and Cooper’s news feeds in January from Pages named “U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders” and “Donald Trump for President” respectively :

In terms of news, Linder follows at least two local media organizations — “WZTV FOX 17 News, Nashville,” where she does not live, and a local hip hop radio station from New Orleans, “Q93.” Cooper has liked at least 23 pages that identify themselves as news or media organizations, and the majority of them are openly right-leaning, with “Clashdaily.com with Doug Giles” and “Nation in Distress” showing up the most in Cooper’s feed.

Here’s a typical post from the Nashville news station Linder follows and a post from ClashDaily.com found on Cooper’s feed from January:

Fake and hyperpartisan news posts also contributed to tensions between Cooper and Linder.

Back in August, Cooper posted a news article titled “BREAKING: 49ers DROPS Kaepernick After He Refuses to Stand for National Anthem” from American Updater, a right-leaning Facebook page, on her own timeline. Linder commented on her mother’s post, pointing out that it wasn’t real news: “First, this is one of those scammy articles we discussed last week (please, for the love of God, stop sharing this crap without verifying its validity). Second, this is false.” The story is no longer available online, and its headline was incorrect.

Screenshot of an article Cooper shared that no longer exists

Cooper’s experience online echoes that of many political news consumers on Facebook, who are increasingly targeted by partisan media makers on both sides of the political spectrum that rely on Facebook to attract readers.

“I'm real bad about reading stuff and not really knowing what fake news [is],” said Cooper about her online behavior during the election. “I'd see something and be like ‘What?’ and get really excited. [And then] Lindsey would be like, ‘This is fake news.’”

“Right now I'm really confused about what's true and what's not true,” said Cooper.

Despite all those ideological differences, however, Linder and Cooper have commonalities: both care about animals — Linder likes the “Companion Animal Alliance,” an animal adoption page, and Cooper likes at least five dog-related pages and both care about issues around the welfare of others. Linder, due to the nature of her work, follows several criminal-justice related pages while Cooper follows a page called “Support Our Military Heroes.”

Below are two exemplary posts from these groups:

The friends who show up on their news feeds

Perhaps more important than what Linder and Cooper choose to follow may be the people they’re friends with on Facebook. Content from pages only constituted about 15% of Cooper’s feed and even less for Linder (almost 10%).

This is largely because Facebook explicitly prioritizes content from friends rather than pages on people’s news feeds.

The people who populate our unique social media worlds set the bar for what we may perceive as ‘common’ or ‘normal.’ They make up our networked information universe. The majority of Americans who are online — 62% of them — receive news from social media platforms. Of all American adults who are on Facebook 76% use the platform on a daily basis.

The graphic below represents the top 20 people who showed up on Linder and Cooper’s news feeds respectively. Their names have been retracted and replaced with descriptions of each person’s relationship to Linder and Cooper.

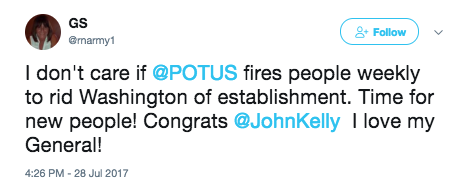

While Linder’s feed was dominated by lawyers, friends from home, and friends she made after leaving her hometown, Cooper’s news feed mostly showed content from people who live near her in a district that voted 61.4% for Donald Trump.

On the left is an article posted by one of Linder’s friends that appeared on her feed. Articles from this person appeared 75 times on Linder’s news feed. On the right is a meme from Cooper’s feed from a friend whose posts showed up 66 times in the data BuzzFeed news analyzed:

Top 15 Facebook Friends Whose Posts Appeared on Linder and Cooper's Facebook News feeds

Lam Thuy Vo

“I think it’s interesting how different our Facebooks are. No matter how different we are, we do have similarities. And on Facebook there’s essentially no overlap in terms of people who we are seeing, pages that are posting,” said Linder.

Both recognized that their daily social media consumption was skewed.

“I hate the bubble and Lindsey pops my bubble every time I come see her. […] I wished I could be friends with everybody on facebook. That way I could see more,” Cooper said.

Not everyone sees it that way. For many, election-inspired unfriending sprees are only widening the rift between people of different political persuasions. With fewer people of opposite political persuasions in people’s social networks, they are less likely to see content posted by others that challenges their own views.

“I'm as guilty as anyone in creating a Facebook bubble. […] Most of the people from back home, some from my family, and a lot of the people from my school are unfollowed on my feed because I don't want to see things that I've come to disagree so strongly with,” Linder said.

When reached for comment, Facebook referred BuzzFeed News to several studies, including an October 2016 Pew survey about the political environment on social media that shows people report seeing a mix of political views in their networks. Another study, which Facebook conducted itself, found that, on average, 23% of people's friends on Facebook claim to have opposing political identities (based on self-reported political affiliation). The company also referred BuzzFeed News to a report from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism that shows social media can actually help diversify a person's news consumption.

According to that same Pew survey Facebook pointed to, more than half (59%) of the study’s participants felt that online encounters with people from opposite political persuasions left them stressed and frustrated, rather than enlightened. Even worse, 64% said they felt like they had less in common with their political counterparts after discussing issues online than they did before.

Cooper holding Linder when she was a baby

Courtesy of Lindsey Linder

Both mother and daughter admit that it’s much easier to discuss their conflicting views when they’re in the same room rather than trying to work it out online.

“We decided that [we share a lot of beliefs] the last time we were together; I felt so good because I don't think any different from Lindsey,” said Cooper.

Linder said, “When I was engaging on something on her Facebook, it was to say, ‘Are you kidding me? I can't believe you shared this.” … And then I went home for a visit and we had a chance to sit down and talk about some political issues. And it was really interesting because it started out as, ‘these are things we would never possibly agree on,’ and by the end of the conversation I felt like we got to a place where we both thought, ‘oh we don't actually disagree.’”

For example: Cooper has a strong anti-abortion stance and thought that she and her daughter would not be able to find common ground, but to her surprise, they were able to agree on some aspects of the subject.

“The thing that actually reduces the number of abortions — access to healthcare, access to contraceptives, comprehensive sex ed — these are the things that actually reduce abortions,” said Linder.

“We […] agreed on that issue,” said Cooper. “When I'm with Lindsey, I'm a Democrat,” Cooper added, laughing.

Quelle: <a href="This Conservative Mom And Liberal Daughter Were Surprised By How Different Their Facebook Feeds Are“>BuzzFeed