So You Got An Amazon Echo. Now What?

If you were one of the people who nabbed a voice-activated, Alexa-powered Echo or Echo Dot when Amazon slashed their prices on Prime Day, you’re probably wondering: What the hell do I do with this thing?

Welcome to the ~future~ of computing. I reviewed the original Echo in February 2016 and have tried every kind of Echo since. After over a year of living with Alexa, here are my best tips for getting the most out of your new smart home tech. Onward!

Right out of the box, think location, location, location – especially if you have an Echo Dot.

Nicole Nguyen / BuzzFeed News / Via Amazon

The Echo’s most powerful feature is being able to hear and process your requests, even if there’s background noise or you’re far away. But its ability to listen depends completely on *where* it is.

Place the device in a central location, as far from the wall as possible. Don’t hide it behind your toaster—or any other appliances or pieces of furniture. Feeling extra? Check out this Redditor’s ambitious ceiling mount or this Imgur user's Echo Dot wall plate.

If you have an Echo Dot, you’re going to need to be even more thoughtful about placement, especially if the Dot is connected to an external speaker. In my experience, it’s better to place the Dot closer to eye level (like a fireplace mantle) and away from the speaker it’s connected to, so it’s better at hearing you over loud music.

If you don’t like the look of the Echo’s black power cord, you can try painting it to match the color of your wall and mounting the cord with small clear cord clips.

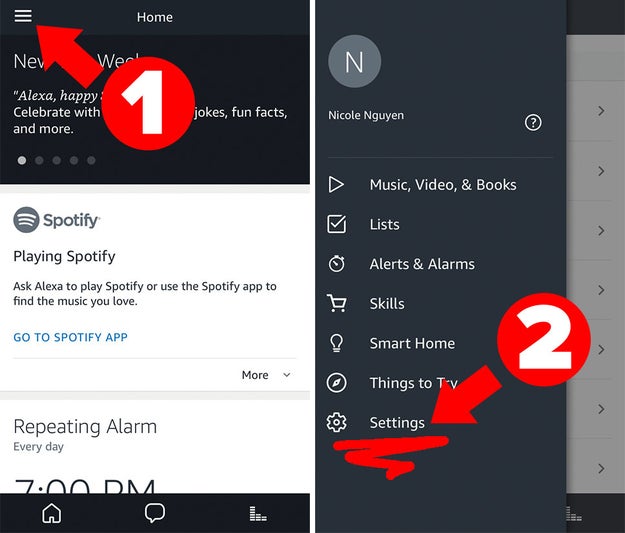

OK – so you’ve set up your Echo. Here are some settings you should take a look at.

Nicole Nguyen / BuzzFeed News

Change the wake word from “Alexa” to “Echo.” It’s less syllables.

CBS Entertainment / Via startrek.com

The wake word is how you signal to your Echo that you’re asking it something. You’re going to be saying whatever word you select a LOT, so choose wisely. If you live in a household with someone named Alex or Alexa, you should definitely change the wake word from Alexa (which is the default) to “Echo.” Plus, it’s a bit easier to say.

Alexa is the default wake word. To change it, open the Alexa app, go to Settings, tap on your Echo device’s name, then scroll down to Wake Word. The options are “Alexa,” “Amazon,” “Echo,” and the Star Trek-inspired “Computer.”

Training the Echo to recognize your voice will help the device hear you.

Voice training will *significantly* enhance your Alexa experience. In the Settings app, scroll down to Voice Training, and select your Echo device from the menu at the top. You’ll then say 25 phrases aloud, which takes about 10 to 15 minutes – but you can pause the training and return to it at any time.

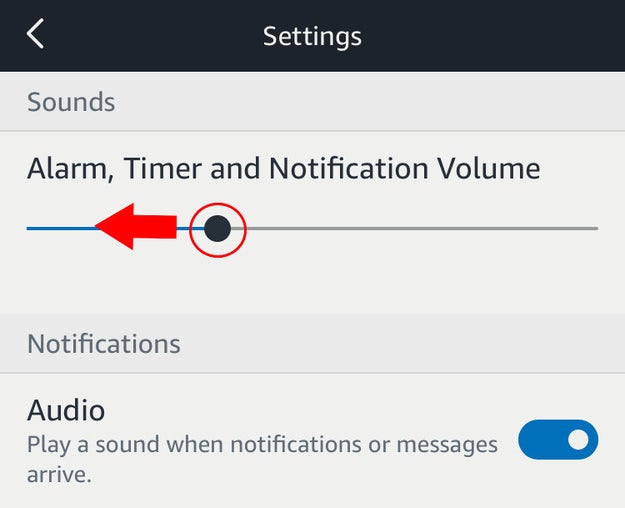

Adjust your Echo’s volume (or prepared to be VERY startled the next time you set an alarm).

Nicole Nguyen / BuzzFeed News

If your Echo is right next to your bed, you might want to lower its notification volume, which was unnecessarily loud when I initially set up my Echo. In Settings, tap on your Echo’s device name > under General, tap Sounds > use the top slider to adjust how loud alarms, timers, and notifications play.

Choose Spotify as your default music service.

Nicole Nguyen / BuzzFeed News

Spotify isn’t the only music service you can connect to Alexa — Amazon Music, Pandora, iHeartRadio, TuneIn, and SiriusXM are also Echo-compatible (sorry, no Apple Music) — but Spotify is certainly the most popular. Alexa’s default music service is the “free” version of Prime Music that comes with Prime, which has a smaller music library than the $8 per month Amazon Music Unlimited Plan. If Spotify is how you usually listen to tunes, you can easily make it your default player in Settings.

In the Alexa app, go to Settings > under Account > go to Music & Media > tap Choose Default Music Services at the bottom. Now you can simply say, “[Wake word], play my Discover Weekly.”

If you use Apple Music or Tidal, you can stream your music by pairing a mobile device to your Echo via Bluetooth. Scroll down to You can play your personal music collection on the Echo to learn more.

You can connect an additional Spotify account by adding another Alexa profile.

Nicole Nguyen / BuzzFeed News

Spotify integration can get a little tricky if multiple people have access to your Echo. For example, if the Echo is only connected to one Spotify account and someone is listening to Spotify on the Echo at home, you won’t be able to listen to Spotify on your laptop at work.

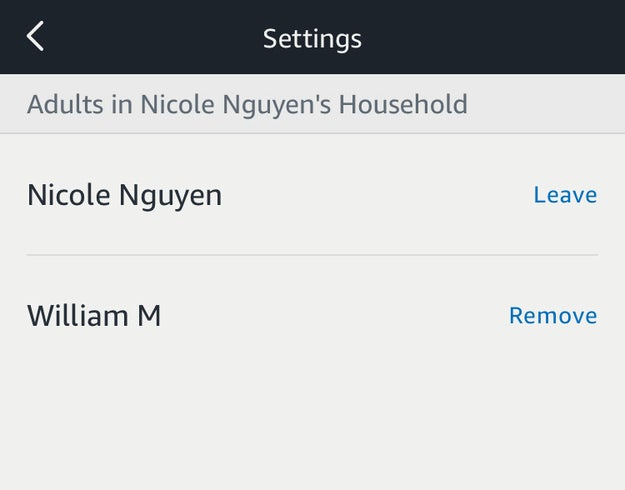

Adding a user to your Amazon household fixes this problem (one household can only have two adults). Go to Settings > under Account > select Household Profile to add another adult to your Amazon Household. Say, “[Wake word], switch accounts” to access the other profile’s Discovery Weekly on Spotify or audiobooks. You can also say “Which account is this?” at anytime.

Careful: If you remove an adult from an Amazon Household, you won’t be able to join another Household or add another adult to your Household for 180 days.

The Echo can also be your new home phone.

You can use the Echo to make or receive calls. The caveat? The person on the other end also needs an Echo device, or the free Alexa app installed on their phone.

Once you set up Amazon’s new Wi-Fi calling and messaging service, the Alexa app will request access to your phone’s contact list and will automatically add all contacts who have signed up for Alexa calling to your Alexa app. To call one of those contacts, you can say, “[Wake word], call [first name/last name],” then Alexa will confirm which person you want to call, and then ping their Echo or mobile device.

It’s important to note that your Echo can’t call 9-1-1 or other emergency services.

When someone calls you, you can say, “[Wake word], answer” or “[Wake word], ignore.” You can block people you’d probably rather *not* call your Echo, by tapping on the “Conversations” tab (the middle icon on the bottom right in the Alexa app) > tap the contact list icon on the top right > scroll all the way down to Block Contacts. And if Alexa calling isn’t for you? Deactivate the service by calling the Amazon help number.

If you have multiple Echo devices, you can use them as an inter-house intercom.

Fox / Via simpsonsworld.com

With this setting enabled, you can essentially use multiple Echos as walkie-talkies. Name each device by room (like, “office” or “kitchen”). Then go to Settings > for each device listed, turn on Drop In > for Only my household. Now you can say, “[Wake word], call the kitchen” or “[Wake word], drop in on the kitchen.”

You can also call these Echo devices from your phone while you’re away from home, by opening the Alexa app and saying the same command (“[Wake word] call the kitchen”).

Speaking of Alexa Calling, schedule “Do Not Disturb” during sleeping hours.

Do Not Disturb prevents Alexa from letting calls through. Your Echo will, however, play alarms and timers. You can say, “[Wake word], do not disturb” or “[Wake word], turn off do not disturb.”

In the Alexa app, you can also schedule the feature. Go to Settings > your Echo device name > under Do Not Disturb, tap Scheduled, then select Start and End times.

Add a confirmation code to voice purchasing.

The Echo can buy stuff for you (because Amazon). You can say things like, “Reorder diapers” or “Order AA batteries.”

The feature is an easy way to make sure you never run out of olive oil, laundry detergent, etc. — but it can also be disastrous. A six-year-old in Texas was able to order a $170 dollhouse and four pounds of cookies through voice purchasing. You do need to say “yes” to confirm the order, but that’s not difficult for a toddler. Protect yourself from accidental purchases by going to the app’s Settings > Voice Purchasing > and under Require confirmation code, enter a 4-digit code.

The Echo can be a great to-do manager, but the Alexa app sucks. Link Any.do or Todoist instead.

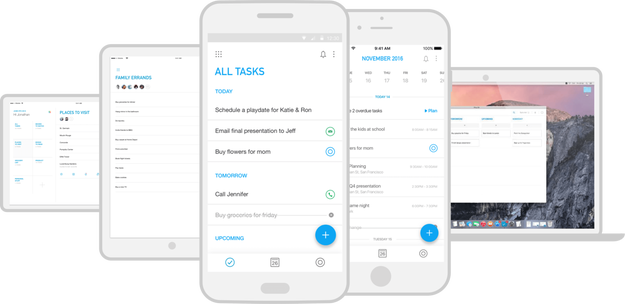

When you need to remember to do something, it’s incredibly convenient to utter “Add ‘Take out the trash tomorrow’ to my to do list” into thin air. But the Alexa app’s built-in to-do list looks a little clunky and doesn’t have many features (like the ability to set a reminder), so try using an Alexa-compatible app instead, like Any.do or Todoist.

Go to Settings > Lists to link an Anydo or Todoist account (Any.do is my personal preference because it’s so well-designed). By connecting your Alexa to-do list to a more robust app, you can set better reminders, add notes, and share and assign individual tasks. In other words, you’ll actually get stuff done.

Now that you’ve fiddled with some of the most important settings – read this post on the most useful, basic Amazon commands.

Nicole Nguyen / BuzzFeed News

Since that article was published last year, I’ve discovered some neat new Alexa uses.

Kindle + Audiobook + Whispersync + Echo = Amazingness.

Nicole Nguyen / BuzzFeed News

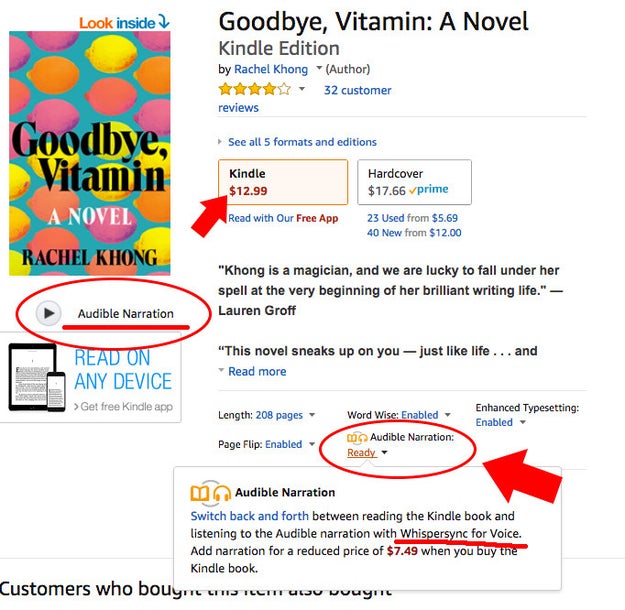

Guys. Synced Kindle and audiobooks are the BEST. You can start reading your Kindle book on your bus ride home, and then, while you’re folding laundry later that night, pick up where you left off via the audio version of that same book on your Echo. THEN, before you go to bed, open up your book on your Kindle (or phone, tablet, whatever) where the audio left off.

Bonus tip: Pair your Echo via Bluetooth to a waterproof speaker and listen to your book while you shower.

It’s the only way I’ve been able to actually finish books this year (seriously). When you search for a book on Amazon in Kindle e-books, the result will read “Whispersync for Voice-ready” under the price, which indicates that title is also available as an audiobook, and can be synced to your Kindle e-book progress. The audiobook add-on typically costs between $6 and $15 and it’s worth it.

You can play your personal music collection on the Echo.

If you have music purchased through iTunes or Google Play, you can access that library via your Echo devices.

There are two ways to do this: The easy way is connecting a phone or tablet to your Echo device via Bluetooth. Say, “[Wake word], pair” and in the Bluetooth settings page of your mobile device, the Echo device will appear as a speaker. You can now play music stored locally on your phone or tablet. It’s also the easiest way to play podcasts if you’re not on the most recent episode.

The slightly harder way is to upload your music library to Amazon Music using the app for PC or Mac. You can sync up to 250 songs for free, before having to upgrade to Amazon Music Unlimited ($8 per month for Prime users).

If you move your Echo between rooms a lot, get an extra adapter. It might need resetting, too.

Nicole Nguyen / BuzzFeed News

Quelle: <a href="So You Got An Amazon Echo. Now What?“>BuzzFeed