AP/Richard Drew

Behind the scenes on what may appear to be a simple product page on Amazon is a bustle of sellers all scrambling to win your business. They're fighting over a small yellow box that is emerging as one of the most important battlegrounds in online shopping.

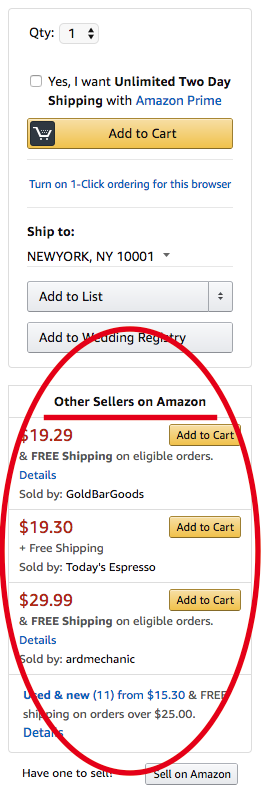

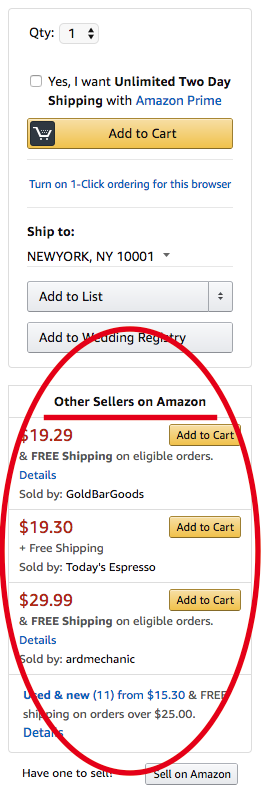

To the average user, who lands on a product page, it's all pretty straightforward. On the left, photos of the item — lets say, a cell phone charger. To the right, there's the “Add to Cart” button. Pretty simple, right?

But dozens of sellers may all be offering that same charger, and only one is chosen by Amazon's systems to get the sale when you hit Add to Cart. The others are relegated further down the page, and the vast majority of Amazon users never bother to look at them.

Amazon

That yellow button, known as the “buy box”, is ultra-prime real estate. For online sellers, winning the race for the buy box is similar to landing the first result on a Google search or, in the brick and mortar world, being displayed in the most visible, highly-trafficked sections of supermarket aisles.

Amazon sellers compete tooth and nail to please the algorithms that determine who sits in the buy box. It's a privilege they earn — and it's not for sale.

“The majority of the sales that occur on Amazon goes to the seller who is in the Buy box, about 85 to 90-plus percent,” said Phillip D'Orazio, president of the Palmetto Digital Marketing Group, which manages Amazon accounts for clients.

Other sellers are listed on the product page, but since customers rarely click through to see their offers, missing out on being the “Add to Cart” vendor, even for a few hours, can mean a serious loss in sales, said D'Orazio.

Unlike other marketplaces like eBay or Alibaba, Amazon pits sellers against each other to win a turn in the Buy box. The exact details of how its systems make the choice are kept secret, but the company tells sellers they can increase their chances by keeping prices low, updating their inventory, offering multiple shipping methods, and offering fast, reliable service. Sellers who have been on the marketplace longer and offer shipping from Amazon's own warehouses also get preference.

That means the Buy box doesn't always feature the cheapest option. Instead, it's a balance of price, service, and Amazon's evaluation of the seller.

“In a lot of ways the Buy box is a slowed down stock exchange,” said Juozas Kaziukenas, founder and CEO of Marketplace Pulse, which collects and analyzes e-commerce marketplace data. “You have a flow of customers who are willing to buy a particular product and they’re willing to pay whatever the market price is, but then there are hundreds of sellers who want to have a sale.”

The idea is such an exchange drives down prices and drives up customer service so that consumers get the best purchasing experience, Kaziukenas told BuzzFeed News. “The Buy box encapsulates the notion that customers are willing to pay market price, but as opposed to setting it by hand let's make the market decide.”

Much like the behind-the-scenes tweaks used by marketers to land the top Google result, Amazon sellers do intensive data analysis, using specialized software that helps land them in the buy box.

“I would tell you that we’re really a data company,” said Alexander Lans, the owner of One Stop Equine Shop which sells its horse riding gear on Amazon as OSO1O. “That's what we are for all intents and purposes. In 2017, most companies are data companies.”

Lans, who has been selling products on Amazon since 2011, told BuzzFeed News that while the company is staffed by horse enthusiasts, its selection of products and whether to sell them on their own site or over Amazon is based completely on data.

“Part of our strategy to win the Buy box is we have a portfolio of products that we’ve structured over time where we have the right products at the right place at the right time,” he said. Lans sells a mix of stable, year-round products, along with ones whose sales move according to seasonal demand. This way, he said, the company builds up a track record of consistent sales and positive customer ratings.

Amazon.com / Via amazon.com

Amazon's buy box algorithms prioritize vendors who pay to house their products in its warehouses, giving the company more control over the shipping process. Lans sends some of his products to Amazon to fulfill and ship, offering many products over Amazon Prime.

Amazon.com / Via amazon.com

Luke Peters, the owner of Air-N-Water.com which has sold its products on Amazon for 13 years, said that he only stores some of his smaller products at an Amazon distribution center to manage his costs. The rest he ships from the company's own 100,000 square foot warehouse.

“If a product is like, the size of a toaster oven or a microwave then you can ship [through Amazon]. If it’s bigger than that, it starts getting too expensive to do,” he said.

Peters, like other sellers, also uses a software called ChannelAdvisor to help keep his prices competitive. While Amazon has a price management tool built into its seller accounts, repricing software has the added advantage of adjusting prices according to shipment costs and other variables, Peters said.

A difference of $0.50 or, sometimes, just a penny can influence your share of Buy box sales, he said.

“Obviously you have to be competitive,” said Peters. “I think a good number to hit is to be under 2% of the best price. You don't always have to win the best price to win equal share of Buy box but if you’re within 1-2% you're going to get an equal share.”

Amazon.com / Via amazon.com

“You have to learn to play the algorithim game rather than just using common sense,” Andrew Tjernlund, who sells gas and electric appliance parts on Amazon under Tjernlund Products Inc., told BuzzFeed News. “Even if they think Amazon is gaming the system, it’s based on real data,” he said.

Marketplace Pulse's Kaziukenas believes in the data. “The Buy box is much smarter than it appears,” he said. “It’s trying to do things beyond the price and trying to help customers. Customers probably should not try to outsmart that. There's a reason why Amazon did not pick another seller.”

Quelle: <a href="There's A War Going On Behind Amazon's "Add To Cart" Button“>BuzzFeed